(Image: In August 2020, Mercy Corps launched the Gaskiya program — named for the word “truth” in the Hausa language — to understand how rumors and misinformation flow through communities in Nigeria and to test measures to prevent their spread. As part of the program, community leaders, known as Truth Champions, listen and report rumors about COVID-19 in their community.)

As every nation struggles to contain COVID-19, one of the most pressing challenges for governments, public health officials, and humanitarians has been the fact that misinformation about the pandemic seems to spread almost as quickly as the virus itself. In nearly every country, conspiracy theories and false narratives abound, from rumors about the origin of the virus and how it is spread, to false advice about how to treat it.

Such misinformation is dangerous in any context, but particularly so in fragile places dealing with conflict, violence and weak governance, where false narratives are often weaponized against marginalized groups. As the extent of this problem became clear earlier this year, Mercy Corps launched a program that seeks to understand how these rumors spread and empower community leaders to share accurate information that can cut through the noise and counter these waves of falsehoods.

In northeast Nigeria, a region where civilians bear the brunt of a brutal conflict between the military and armed opposition groups, an assessment by a local radio station in May 2020 found that 96 percent of listeners had heard COVID-19 messaging on the station, but a full 45 percent still did not believe the virus was “real or deadly.” Rumors abound, including that the virus cannot survive in the hot climate of northern Nigeria or that it is a test from God. In August, Mercy Corps launched Gaskiya (named for the word “truth” in the Hausa language), a program designed to understand how rumors and misinformation flow through communities here and test measures to prevent their spread.

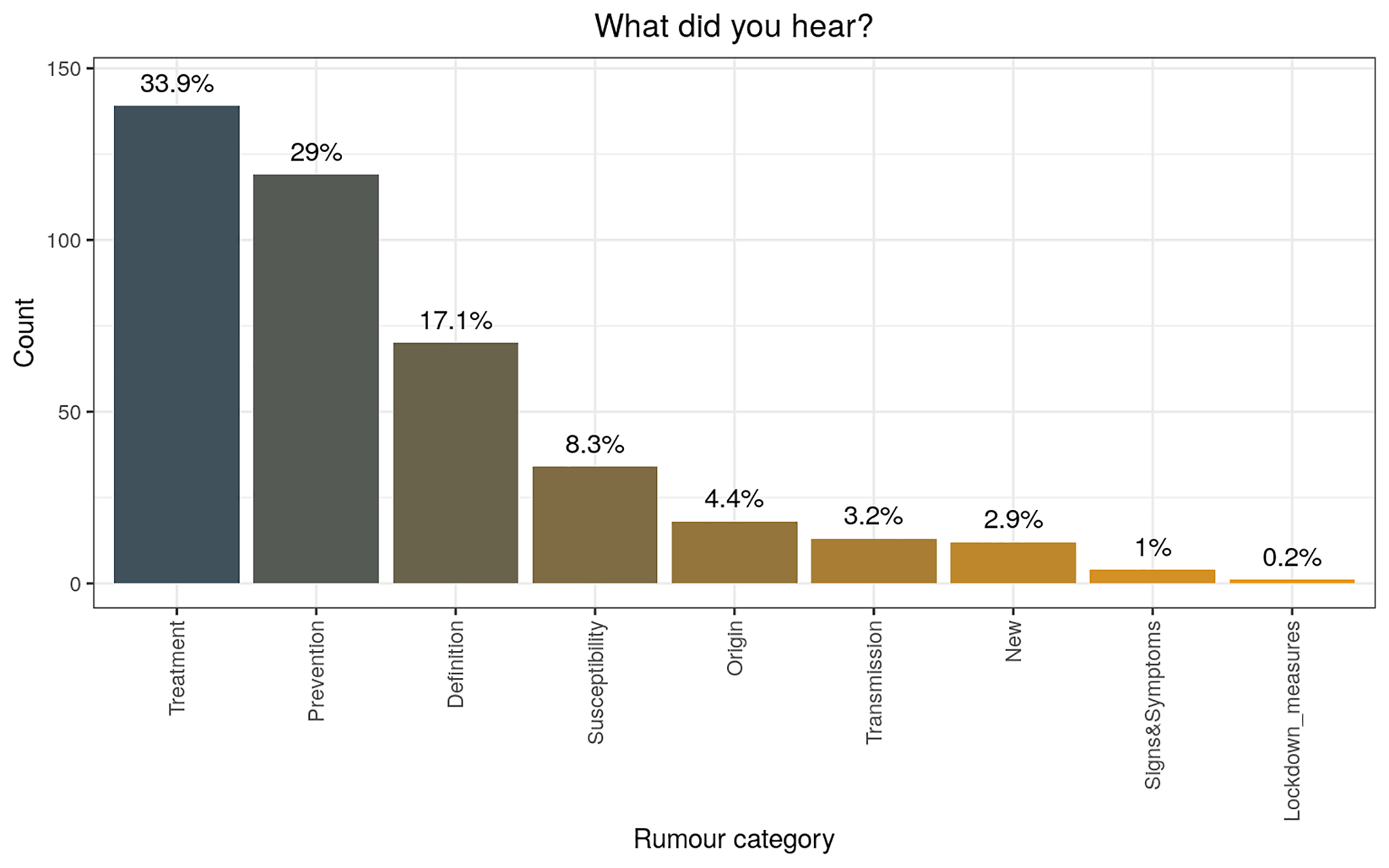

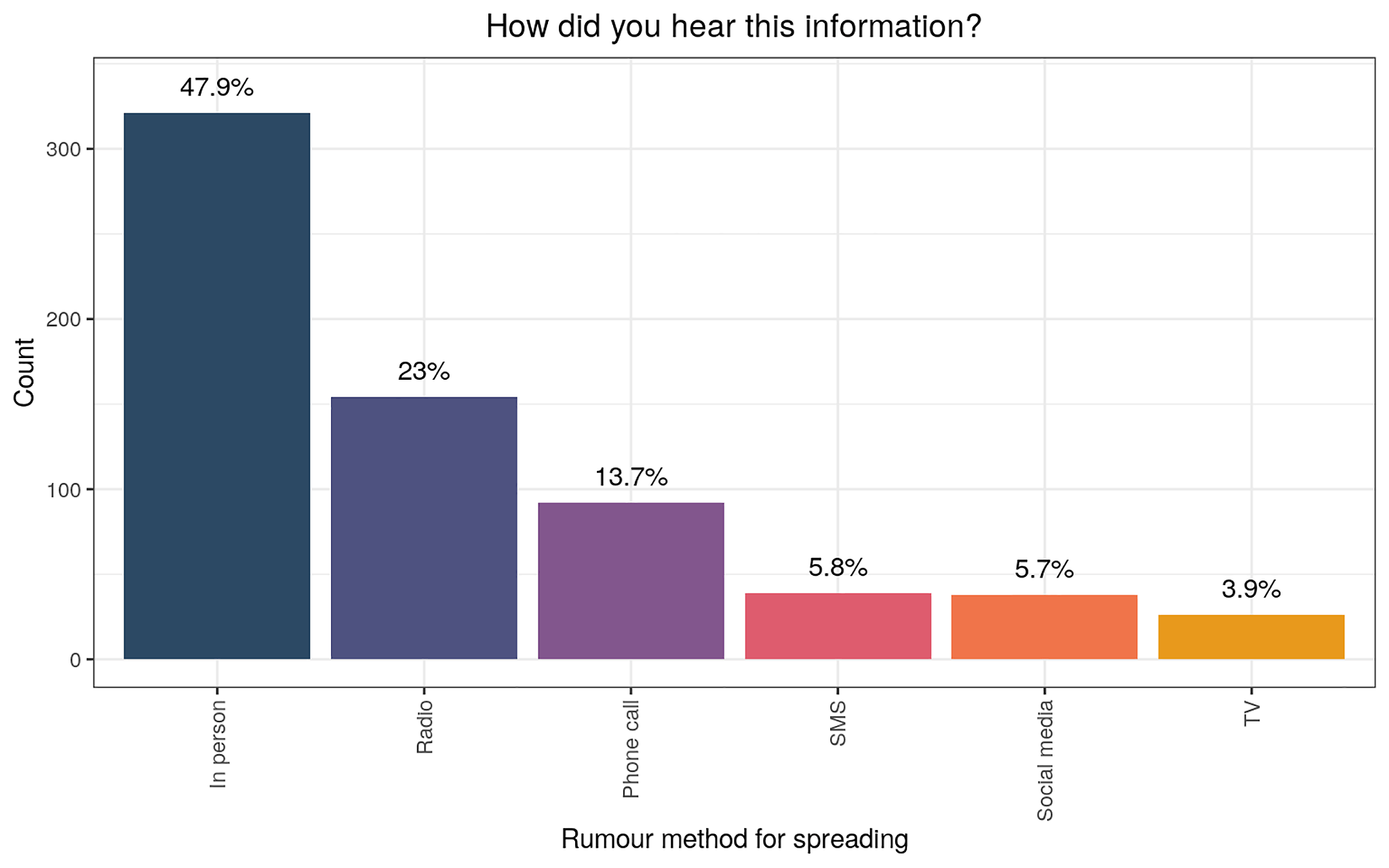

Because there is so much misinformation out there, our team didn’t think that just providing correct information would be enough. We needed to better understand the rumor landscape — where they were coming from, who was spreading them — before we could figure out how to best counter them. We began with a household survey in nine different communities, designed to gain an understanding of what exactly people were hearing about COVID-19 and where they were hearing it. Then we designed a user-facing rumor tracker that allows citizens to report rumors they hear in their communities via SMS text messages and calls. We recruited 178 “Truth Champions,” representing each of the nine different communities, and trained them on the truth about COVID-19, how to identify rumors, and on how to use the tool itself.

We chose a phone and SMS-based platform because smartphones and apps are not widely used in these areas. When someone calls into the tool to report a rumor, we ask them what the rumor is, where they heard it and from whom. Our partners at Translators without Borders created a dashboard to conduct qualitative analysis of the rumors, analyzing trends in what’s spreading and from where. Meanwhile, after each report, the Truth Champion gets a phone call back with information about how to refute that particular rumor.

In addition to that immediate feedback loop, perhaps the most crucial element of this project is the last step: bringing that data and analysis back to each community in an effort to find solutions. In each location, we bring the Truth Champions and other community leaders together to discuss what we’ve observed so that we can better understand why certain rumors are resonant in each location, and work with them to identify how we can best combat these rumors.

In our first few weeks since launching Gaskiya, we’ve already seen a wide range of rumors, including that the virus doesn’t exist at all. Some suggest a variety of unproven home remedies, while others heard from religious leaders that the virus could be fought off with greater faith. These are the kinds of rumors and misinformation about COVID-19 that we’ve seen, with varying details, all over the world. The key is figuring out how to gain trust and combat misinformation in each local context.

We know from our experience in fragile places around the globe that the most effective solutions come from the local community and those experiencing the challenges firsthand. So while Gaskiya relies on technology to operate, it really is about listening to people. The technology doesn’t solve the problem, but it does give us a path to finding human-centered solutions for each community.

In recent years there’s been a growing emphasis in the humanitarian community around the belief that access to information is a human right. Initiatives like Signpost (a Mercy Corps collaboration with the International Rescue Committee), Internews, and NetHope are all built on the idea that for many vulnerable people, access to information can often be a life-or-death issue. The rapid spread of misinformation during the pandemic has highlighted that people need not only access to information, but also the resources to interpret, analyze and respond to that information.

As the world looks toward the successful global rollout of COVID-19 vaccines, community engagement and trust-building will be critical. Misinformation about the vaccine is already circulating in the countries where we work, before vaccines have even arrived. One of the biggest hurdles will be convincing people that vaccines and those providing them can be trusted. Winning this trust and tackling the misinformation that creates vaccine hesitancy will require significant funding and a herculean and coordinated effort from governments, public health experts and humanitarian groups.

To do that, we need to meet people where they are, digitally speaking. The tech we use will vary by context, and any initiative needs to take the reality of the local digital ecosystem into account. In northeast Nigeria, that means using phone and SMS technology. In another setting it might be Facebook or WhatsApp. And notably, tech alone isn’t the solution. But when used smartly, the right tech allows us to effectively listen to people and find out exactly what they need.

This article series is sponsored by Cisco and produced by the TriplePundit editorial team.

Image credit: Mercy Corps

Alexa Schmidt is the Interim Director of Mercy Corps’ Technology for Impact program, which aims to develop better processes and experiment with innovative tools to deliver aid faster, more efficiently, and to more people. Three years into the program, it has reached nearly 7 million people with information dissemination activities, WiFi access, and improved digital cash and voucher systems. She previously worked with Mercy Corps, covering Syria, Yemen, and the European refugee crisis. Prior to her international development career, Alexa worked in refugee resettlement in the U.S., where she helped school districts and local resettlement agencies integrate refugee youth into the U.S. school system. Alexa has lived and worked in Bangladesh on a Fulbright Scholarship and completed her MSc in Comparative and International Education from the University of Oxford with a focus on access to higher education for refugees.