What if there were a better way to produce beef - one that actually reduces atmospheric carbon? This fourth-generation cattleman explains why he believes he has found an answer.

Beef has a bad name these days. The kind of beef, that is, that comes from cows, not the plant-based alternatives from Impossible Burger and Beyond Meat getting so much buzz lately.

A key reason for beef’s bad rap is its large carbon footprint: The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that livestock is responsible for at least 14.5 percent of greenhouse gases being released worldwide.

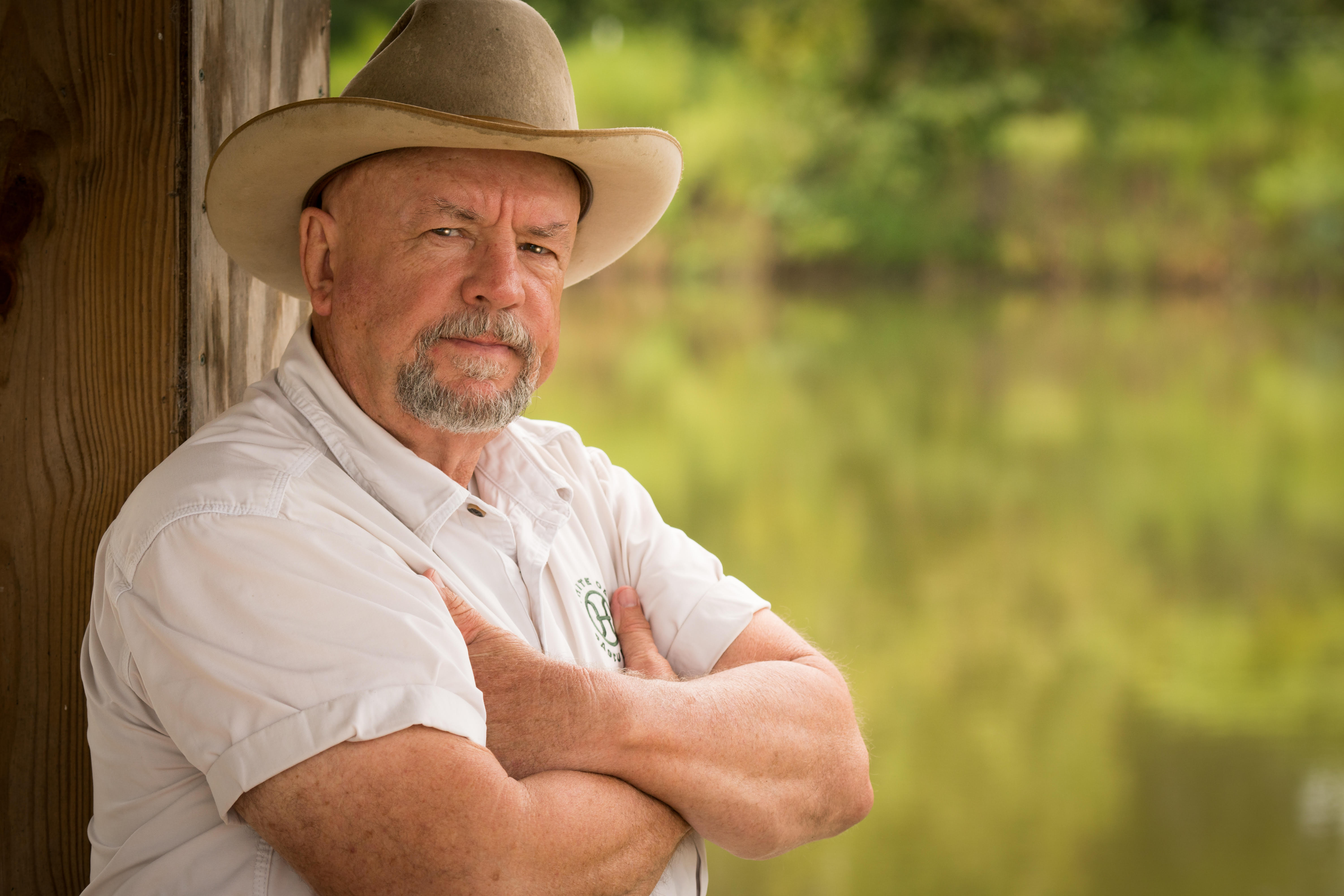

But what if there were a better way to produce beef—one that actually reduces atmospheric carbon? Fourth-generation Georgia cattleman Will Harris (pictured below), owner of White Oak Pastures, believes he has found the answer “by coming full cycle to the way my grandfather and great-grandfather farmed the land,” he told TriplePundit. “We call it radically traditional farming.”

In 1995, Harris transitioned his conventional farm operations to a grass-fed, pastured program. Now a recent Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) study by environmental research firm Quantis has found that White Oak Pastures is offsetting at least 100 percent of the farm's grass-fed beef carbon emissions and as much as 85 percent of the farm’s total carbon emissions. Instead of producing net emissions, Harris says his grass-fed cattle sequester more carbon than they produce.

Using both soil sampling and modeled data from 2017, the LCA analyzed the farm’s overall greenhouse gas footprint. The study included enteric emissions (belches and gas) from cattle, manure emissions, farm activities, slaughter and transport, and carbon sequestration through soil and plant matter.

The LCA was funded by General Mills, which is working with White Oak Pastures on regenerative agriculture practices. White Oak Pastures is a key supplier for Epic Provisions, General Mills’ U.S. meat-based snacks business.

Healing the land

“Going back to the older ways was about healing my land from years of centralized, commoditized, industrialized farming. It was about caring for my animals and helping my local rural community,” Harris said. “The carbon sequestration was a pleasant, unintended benefit.”

In the past 25 years, Harris has transitioned from 0.5 percent to 5 percent organic farming, he said, and his revenues have increased from $1 million to $20 million. And his operation has grown from three employees making minimum wage to 165 employees “making twice the county average in one of the most impoverished counties in Georgia,” he added.

Harris said his practices, like grazing small ruminants such as sheep together with cows, have helped keep his animals healthier. The soil has gone from 1 percent soil organic matter to 5 percent. Water retention in the soil is also better, he said. There’s greater biodiversity, he added, including the return of bald eagles.

The “save more than you spend” carbon model on Harris’ zero waste farm doesn’t have to be radical, he argues.

“But I only have 3,200 acres. We need a lot more farmers to do this. No one set out to ruin the land or harm the animals or impoverish our rural communities. But collectively we decided we wanted really cheap, really abundant food, and in the narrow efforts to make food cheap and abundant through centralization, commoditization and industrialization, we sacrificed the rural economy and the degradation of the land and the welfare of the animals.”

Harris believes that consumers will have to play the most important role in driving a transition in beef production that is less harmful to the climate. “I won’t be able to influence another farmer. I can show them what I do, but it’s consumers who have the influence,” he said.

Lower carbon footprint than plant-based alternatives

“The results from the White Oak Pastures’ LCA turns conventional wisdom about beef on its head,” Shauna Sadowski, senior sustainability manager for the natural and organic business unit at General Mills, told 3p.

“Not only is White Oak Pastures beef lower in carbon emissions than conventional beef, it also has a smaller carbon footprint than other non-beef protein sources, including Impossible Burger and Beyond Meat,” Sadowski said, citing the plant-based meat companies' own public LCAs. “Through this LCA on White Oak Pastures, we see the potential for what is possible through holistic land stewardship.”

The FAO’s Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock report shows that a 30 percent reduction in livestock GHG emissions are within reach—if “producers in a given system, region and climate adopted technologies and practices currently used by the 10 percent of producers with the lowest emissions intensity.”

Such practices, the FAO said, “are not widely used today.”

Image credit: White Oak Pastures

Based in Florida, Amy has covered sustainability for over 25 years, including for TriplePundit, Reuters Sustainable Business and Ethical Corporation Magazine. She also writes sustainability reports and thought leadership for companies. She is the ghostwriter for Sustainability Leadership: A Swedish Approach to Transforming Your Company, Industry and the World. Connect with Amy on LinkedIn and her Substack newsletter focused on gray divorce, caregiving and other cultural topics.