Think of engineered microbes as a kind of living software, and you have an idea where the company LanzaTech is going with its carbon capture and recycling technology. The company specializes in a system that recovers emissions and converts them into ethanol and other building blocks for liquid fuels and synthetic materials including plastic and rubber. That's a significant improvement over the conventional formulation of carbon capture, which gets to the "capture" phase and stops there.

Last month Triple Pundit spoke to LanzaTech's head of communications and government relations Freya Burton for a look at the future of carbon recycling, and it looks like the company's approach is well-timed to take advantage of emerging trends in recycling and waste recovery.

What's all this about robust bugs?

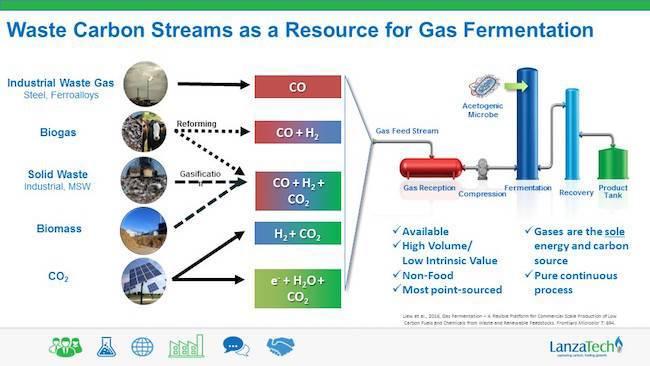

LanzaTech pops up regularly on the Triple Pundit clean technology radar when it comes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and for good reason. The company has developed a unique carbon capture and conversion technology based on the natural process of fermentation.Fermentation is the means by which microbes convert plant sugars to ethanol. The LanzaTech process skips over the middleman and goes straight to the carbon dioxide that plants use to convert solar energy into plant sugars.

The inspiration for LanzaTech's system comes from naturally-occurring acetogens, an ancient family of gas-fermenting organisms found near undersea hydrothermal vents. The vents provide acetogens with all the nutrients they need for their entire lifecycle, in the form of gases.

The vent gases have much in common with emissions from steel manufacturing and other industrial and landfill sources, namely carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide as well as hydrogen, hydrogen sulphide and methane. That's what caught the attention of LanzaTech, which was founded in 2005.

It took some tweaking, to come up with a strain of "robust bugs" that can survive -- and thrive -- in industrial waste gases, but the company did succeed in engineering its own version of the microbial family to produce products like jet fuel and diesel.

The technology has also caught the eye of several key partners including the US Department of Energy, which chipped in with $4 million in funding back in 2016 to help ramp up a demonstration facility here in the US.

Carbon capture good, carbon upcycling better

Check out a 2013 Triple Pundit video interview with LanzaTech CEO Jennifer Holmgren for more background on LanzaTech's clean tech. At the time, the company was focused on China. More recently it has expanded elsewhere in the globe, one highlight being the US. LanzaTech now has an office in Chicago, a research partnership with the Department of Energy and a commitment for a demonstration scale biorefinery that will produce jet fuel and diesel from industrial waste gas.

"We've branched out," Burton explained in last month's phone interview, "But for now we're still staying with ethanol. It can be converted to jet fuel, ethylene and polyethylene. We can also demonstrate isopropyl alcohol and 20 other chemicals."

Burton also dropped a hint about the role of the LanzaTech process from the bottom line perspective:

It's another way of recycling carbon, and it can be locked into a proper circular economy.

In other words, reclaiming carbon for high-value products could make carbon capture economical. That's an important step beyond the conventional approach of carbon capture and sequestration.

The shortcomings of carbon capture were vividly illustrated in 2015, when the US Department of Energy pulled the funding plug on the much-touted FutureGen "clean" coal carbon capture and sequestration project. FutureGen launched under the Bush administration to great acclaim in 2005 and was supported by the Obama administration with a $1 billion pledge, but it ran out of steam after private sector partners took a cold, hard look at the economics.

Microbes as software

LanzaTech has not lost its interest in industrial waste gas, but it is currently focused on municipal solid waste (MSW) as a feedstock.

That makes sense for a variety of reasons, including stability of supply. Factories can come and go within a few years, but cities -- and their waste -- have far more staying power. It also makes sense for markets like the US, which are seeing industry shrink while becoming less dependent on coal and diesel power.

In the broader arena of recycling, the challenge of MSW is that it exposes municipalities and/or their contractors to the global commodities market. Until now, one relief valve was the globe itself. Recyclers could ship scrap literally around the world in search of markets. China recently threw a monkey wrench into that strategy, though, by banning two dozen kinds of scrap imports.

One result of China's clampdown is that municipalities have more incentive to seek out recycling streams that can be used locally. That opens the door for more waste-to-energy conversion.

In the past that meant incineration, but waste-to-energy is becoming far more sophisticated. Landfill gas is one increasingly common MSW resource recovery strategy. The recently opened Hiriya Recycling Park in Tel Aviv, Israel, stepped up the strategy by recovering gas from an adjacent landfill, biogas from recovered organic material in MSW, and carbon-rich fuel consisting of scrap separated from the mixed waste stream. These energy products are used by two local factories. Here in the US, Dow has also ramped up the waste-to-energy approach by partnering with cities to recover hard-to-recycle plastics for processing into diesel fuel.

The new waste-to-energy strategy is an improvement, but generally it ties the facility to a single product or group of products. That's where the idea of microbes as software comes in. Burton explains the advantage of a production system that can rapidly switch products. Like a computer responding to different programs, the expensive hardware remains the same. The software can be switched in and out seamlessly, at less expense than building a new facility (following comment edited for flow):

"We can change the bugs. They're the 'software.' To produce the different products using the same equipment, we just change the bugs. It only takes about 24 hours, and it makes our system disruptive. It speeds up chemical production to respond quickly to the market.

Burton also contrasts the 24-hour changeover timeline with conventional refinery retooling:

"It takes five to ten years for permitting and planning conventional facilities. The flexibility of using waste as a feedstock means that you're not tied to fossil fuels..."

The LanzaTech system could also piggyback on existing waste-to-energy facilities. The company has been working with Sekisui Chemical Co. on a project that diverts and "upcycles" some of the syngas generated by an existing gasification system at a landfill in Japan. Here's the rundown from LanzaTech:

In contrast to traditional fermentation that uses yeast to convert sugars into products such as ethanol, LanzaTech ferments gases and produces ethanol and a variety of chemicals using a naturally occurring bacteria. These chemicals are precursors to plastics, rubber and synthetic fibres and can be used to produce new packaging, sneakers, cell phone covers and yoga pants while avoiding the need for more fossil resources to come out of the ground.

That certainly provides MSW stakeholders with a range of marketing options.

What about clean coal?

As for "clean" coal, the Energy Department still hasn't given up. Part of FutureGen's problem was technological, and the agency is still committed to improvements with a new $44 million pledge for improving carbon capture at coal power plants.

That's all well and good, but that may not be good enough to save the US coal industry. Even if the Energy Department-funded research pans out, there's no guarantee that coal power plants will be in position to invest in the new equipment.

Coal power plants in the US have been tumbling like dominoes. That's mainly because cheap natural gas, and more recently low cost renewables, don't favor the bottom line for upgrades to aging coal facilities.

Despite President Trump's frequent pledges to support coal miners and coal stakeholders, the Trump administration will see its first coal mine close this spring, and industry analysts predict that the pace of coal plant closures will accelerate this year.

Image: via LanzaTech.

Tina writes frequently for TriplePundit and other websites, with a focus on military, government and corporate sustainability, clean tech research and emerging energy technologies. She is a former Deputy Director of Public Affairs of the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, and author of books and articles on recycling and other conservation themes.