The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has yet to release firm data on the amount of petroleum products and other toxic substances Hurricane Harvey unleashed on the Texas environment. According to a database kept by the U.S. Coast Guard, though, the numbers are already adding up to one of the worst environmental disasters in the U.S. in recent years.

The U.S. Coast Guard Has The Numbers On Harvey Spills

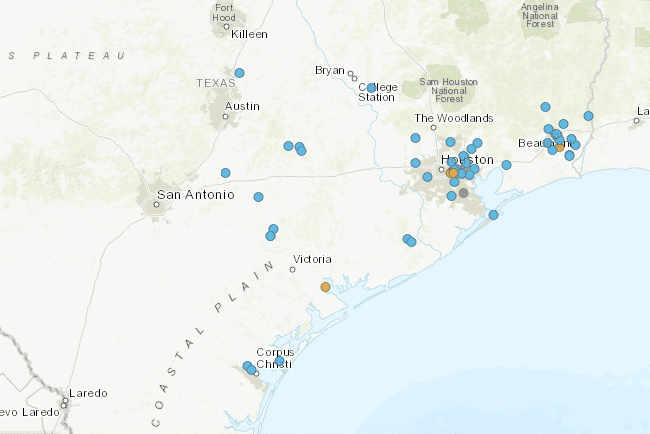

The organization Environmental Integrity Project has compiled the Coast Guard data into an interactive map of toxic spills, including about 100,000 gallons of glycerine and 80,000 gallons of methyl alcohol.

The largest single spill consisted of unleaded gasoline that flooded into the Houston Ship Channel from the Magellan Pipeline Company.

The EIP map adds some firm detail to another data-driven map created by the Union of Concerned Scientists, which lists 650 facilities potentially impacted by Hurricane Harvey. That list includes hundreds of wastewater treatment plants, an unknown number of which have released untreated sewage and industrial waste after Harvey.

Unfortunately, the Coast Guard data only present part of the picture. Its database includes reports of "significant" land and water spills that the Coast Guard received from August 24 to September 8.

These land and water reports are required by federal law (other reports are compiled by EPA), but Texas Governor Greg Abbott added a heavy dose of unnecessary confusion to the picture on August 23, days before Harvey struck, when he issued a proclamation authorizing a temporary waiver of reporting requirements.

In the same proclamation Abbott admitted that he actually had no authority to waive federal regulations, but the damage was already done. An unknown number of facility owners and managers may have taken him at his word.

In addition, according to EIP the Governor also waived certain state regulations without the legal authority to do so:

Some of the state laws the governor waived are also federal requirements. For example, all of the Texas state air pollution reporting requirements contained in Governor Abbott’s proclamation are also contained in federal law. Industrial sources, therefore, have been and remain under a legal obligation to report all releases of contaminants.

Reuters also took a look at the Coast Guard database and came up with a total of more than 22,000 barrels of crude oil, petroleum products and other chemicals released into the environment, including 365 tons of sulfur dioxide, ammonia, toluene, benzene, and other harmful substances.

Other additional impacts noted by Reuters include 27 million cubic feet of natural gas, 1,000 tons of asphalt, and "unknown quantities of other substances."

EIP points out that the failure to report is not just a numbers game:

Reporting all pollution before, during, and after a crisis is critical to protect the public and the emergency responders who rely on the information to protect themselves from harmful exposure. In addition, pollution reports help local, state, and federal officials identify and prioritize neighborhoods, waterways, and businesses that need to be monitored or cleaned up.

So far the known quantities are far below the 190,000 barrels of oil spills racked up by Katrina along the Louisiana coast, but EPA has yet to disclose its data.

Until state and federal agencies get a firm handle on the impact, Texas's ability to recover from Harvey and plan effectively for the next weather emergency will be crippled.

Creating a culture of preparedness

The Washington Post has a good long form article on the many complexities involved in hardening coastal communities like Houston against storms. Do read the full article for details. For those of you on the go, the gist of it is that it is that the general public needs to come around to realizing the high risks involved in coastal living and prepare accordingly.The Post cites FEMA administrator William "Brock" Long, who emphasizes the need to embed long term planning in the national consciousness:

“We need a true culture of preparedness,” he said.

Quite a bit of media attention has been focused on the lack of preparedness at commercial, industrial and Superfund sites in Harvey's path, but the cumulative release of toxic substances from ordinary households could also add up.

The list includes any number of of household cleaning supplies, toiletries, craft and hobby supplies, supplies related to home-based businesses, paints and other home repair materials, yard care supplies, and pool chemicals.

The good news is that benign alternatives to hazardous household products are coming into the mass market. Although transitioning them to universal use is a long, complicated and highly granular endeavor, it is not an impossible one.

Transitioning to flood-resistant building codes is another solution within the realm of possibility.

Florida revised its building codes after Hurricane Andrew devastated the state in 1992, and the stricter standards seem to have helped some buidings survive Hurricane Irma's impact.

A broader solution is also gaining more traction among planners in the aftermath of Harvey: invest more taxpayer dollars in drainage systems, pumps and other flood mitigation infrastructure, and buying out homes or relocating entire neighborhoods that experience chronic flooding.

Planners can plan, but mustering the political to accomplish major infrastructure projects is another matter.

That task is especially difficult in cities where local zoning laws are lax or non-existent, as the Post explains:

Earlier warnings against Houston’s unchecked building explosion have come back to haunt it yet again, environmentalists and civil engineers said this month, attributing part of the flooding to the city’s lack of adequate drainage and excessive building in areas of known risk.

Perhaps lessons learned in Florida will help Houston officials make a better case for risk mitigation.

Still, developing public support for new taxpayer investments -- and a new ecosystem of rules and regulations -- is a tough row to hoe in a culture that has long been groomed to reject taxes, rules and regulations.

Image (screenshot): via EIP, interactive map of spills based on Coast Guard reports.

Tina writes frequently for TriplePundit and other websites, with a focus on military, government and corporate sustainability, clean tech research and emerging energy technologies. She is a former Deputy Director of Public Affairs of the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, and author of books and articles on recycling and other conservation themes.