A harbinger of Donald Trump’s election occurred two years ago in India, when a wave of populism and frustration with the system led to Narendra Modi’s swearing in as India’s prime minister. Like Trump, Modi promised to boost manufacturing, revamp the country’s infrastructure, slash bureaucracy and fight corruption.

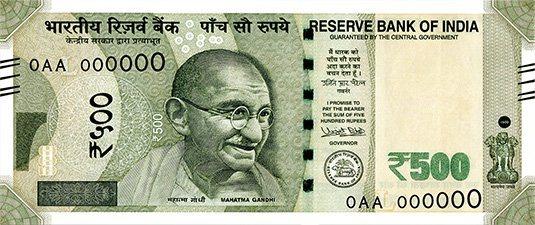

On that last point, Modi announced in a televised address this month that the world’s second most populous country would undergo shock treatment in a move to boost tax collection and increase transparency. The country’s 500- and 1,000-rupee banknotes would no longer be legal tender, and would be replaced with new 500- and 2,000 bills. Citizens have the rest of the year to deposit their older notes, but limits were imposed on how much old currency could be exchanged.

The demonetization policy was presented as a way to expose those with copious amounts of “black money,” although the Modi administration also claimed the old 500 and 1,000 notes were being counterfeited to fund terrorism. But if Modi is going to pay for his ambitious domestic policy agenda, he will need funds – and estimates suggest that less than 1 percent of the country’s 1.2 billion citizens pay taxes.

The logic follows that a large bank account translates into big income, which means more people will be forced to pay their fare share of taxes. And if more money is held in banks, Modi's administration thinks more citizens will pay for goods and services digitally instead of with paper.

The evidence suggests, however, that while the idea has merit, the execution has gone awry – and not just because the digits printed on the new 2,000-rupee note are numerals not permitted by India’s constitution. This currency recall is part of Modi’s plan to extract money illegally stashed abroad in order to redistribute it to India’s poor – but so far Modi’s gamble may be hurting those who have long struggled within the country’s economy.

First, Modi’s plan does not do anything to address wealthy Indians’ money that is sequestered overseas. In addition, the appeals to deposit that money ring hollow in a country where 90 percent of all transactions are conducted in cash. And as the BBC reported, the notes in question represent at least 86 percent of the country’s banknotes in circulation. Many Indians are unbanked; culturally, millions do not trust the country’s financial system and prefer to keep their funds hidden at home. Those who have the means may very well have amassed wealth without paying taxes on it, but much of that money has since been converted into property, gold and jewelry.

The sudden change in currency leaves India’s rural poor most vulnerable. Many of these citizens do not have a bank account, nor do they have the phone or wireless service needed to take part in the emerging digital economy. As economist Rajiv Biswas explained last week in an interview with Deutsche Welle, Modi’s reform is punishing the poorest citizens as they can no longer buy what they need with bank notes that have become suddenly worthless. Wealthier citizens, however, can ride this out. After all, they most likely can tap into gold bullion or foreign currency.

Incidentally, this currency reform will cause a massive waste problem for India, as those 20 billion notes to be taken out of circulation will have to be shredded and dumped at landfills. That imagery will no doubt stick in the minds of many Indians, as they feel Modi has accomplished little with this stunt other than trashing the economy.

Goldman Sachs has reportedly revised its economic forecasts for India, knocking it down almost 1 percentage point as the shortage of cash will most likely dampen economic activity for several months.

Image credit: Reserve Bank of India

Leon Kaye has written for 3p since 2010 and become executive editor in 2018. His previous work includes writing for the Guardian as well as other online and print publications. In addition, he's worked in sales executive roles within technology and financial research companies, as well as for a public relations firm, for which he consulted with one of the globe’s leading sustainability initiatives. Currently living in Central California, he’s traveled to 70-plus countries and has lived and worked in South Korea, the United Arab Emirates and Uruguay.

Leon’s an alum of Fresno State, the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and the University of Southern California's Marshall Business School. He enjoys traveling abroad as well as exploring California’s Central Coast and the Sierra Nevadas.