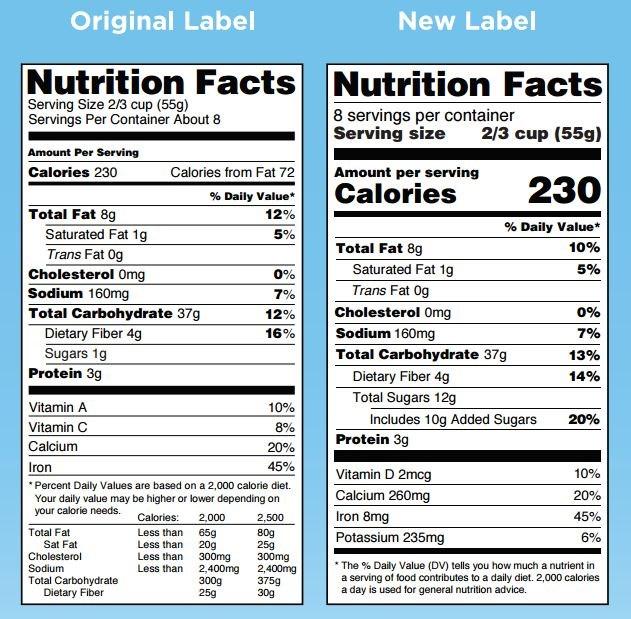

A comparison of the current nutrition label and a new one the FDA proposed.

It’s been nearly 25 years since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandated that all food and beverage packaging carry the Nutrition Facts panel. These labels, now found on over 700,000 products, provide the consumer with information like serving sizes, calories per serving, ingredients and nutritional content.

The original idea was to help people make informed choices about the types and amounts of food they eat, especially for those with particular dietary needs who want to avoid foods high in things like saturated fat, sugar, sodium or cholesterol.

According to the latest research from the FDA, 77 percent of all U.S. adults say they use the Nutrition Facts label always, most of the time, or at least some of the time to learn about the contents of a product. But does this information help reduce the incidence of diet-related chronic diseases like obesity and diabetes? If you ask health experts this question or review the available research, you’ll get a range of answers from yes to maybe to definitely not.

Most experts agree, though, that the labels could be improved from their original format. Consequently, in May 2016, the FDA released a proposal to update the labels to enhance their usefulness and to reflect the latest nutritional research.

For a start, the “Serving Size” section of the label will be changed to more accurately reflect the actual portions consumed by the typical American. This was a big area of confusion for consumers, according to Julie Culp, a manager at General Mills in the North America Labeling and Regulatory Compliance group. The new labels “will be based on the latest dietary intake research that demonstrates what common or average consumption actually looks like,” she noted.

For example, a 20-ounce soft drink will now be labeled as a single serving because most people will consume this amount in one sitting. At the same time, the nutrition facts will change to align with this larger serving size amount.

The new labels will no longer list the amounts of Vitamin A and C in the product, because the latest research shows that most Americans are not deficient in these nutrients. Instead, the amount of Vitamin D and potassium will be listed, two nutrients where many Americans diets are deficient.

The new labels will also reflect the latest research on the link between sugar and disease—particularly obesity—by showing the amount of “added sugars” in a food product, which are defined as “caloric sweeteners with no nutritional value.” This change reflects the U.S. Dietary Guidelines’ recommendation to eat no more than 10 percent of total calories from added sugars. This works out to about 50 grams of added sugar per day for someone on a 2,000 calorie diet.

Food manufacturers with annual sales exceeding $10 million have until January 2020 to update their packaging with the new labels, while the deadline for smaller manufacturers falls a year later. Many have already rolled out the new labels on their packaging.

While debates will continue over how to improve food labeling, there is general agreement that the labels are a good thing for consumers. As John Mackey, CEO of Whole Foods, once said, “People have a right to know what is in their food.”

This effort to increase transparency is less clear cut when it comes to disclosing some ingredients, such as genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Consumers overwhelming support (89 percent) mandatory labels on genetically modified foods. This prompted states like Vermont to pass laws requiring GMO labeling and other states to consider such legislation. At the national level, in July 2016, President Barack Obama signed into a law the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard (NBFDS), which directed the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to establish a national standard for disclosing when a food product contains "bioengineered" ingredients. The USDA issued its final rule for these standards on December 21, 2018.

The NBFDS represents the first mandatory standard for such labels at the national level and will preempt regulations already passed at the state level. Again, large food producers will have until January 2020 to comply, while smaller producers will have until January 2021.

Read the available commentary, and practically none of the consumer groups are happy with the NBFDS standard. In fact, it has been dubbed the DARK Act for “Denying Americans the Right to Know,” which strikes a blow for food transparency. Jeffrey Smith, executive director at the Institute for Responsible Technology, calls the new national standard “a blatant attempt to help food companies hide the GMO content from concerned consumers.”

While many companies in the food industry have resisted mandatory labeling, others have taken a more proactive approach by voluntarily disclosing which of their products are GMO-free. The leading voluntary labeling standard is offered by the Non-GMO Project, an advocacy group that provides a widely-used verification process for determining GMO content.

To comply with the new national NBFDS standard, companies that have already verified their products through credible schemes like the Non-GMO Project will not be required to provide additional verification. General Mills, for example, has several of its brands enrolled in the Non-GMO Project.

The bottom line is that regardless of where one stands on the safety of bioengineered foods and other ingredients, consumers should at least be able to make informed decisions about their food and know their options.

Clearly, consumers do have a right to know what is in (or not in) their foods. However, the debates on the best way of achieving this transparency will likely continue for some time.

Image credit: Pixabay

Jim Witkin is a writer based in Silicon Valley and London focused on business, technology and the environment. His work has been featured in the New York Times and Guardian newspapers. He holds an MBA in Sustainable Management from the Presidio Graduate School.