Firefighters assess the damages after wildfires spread around Los Angeles earlier this month. (Image: Venti Views/Unsplash)

The Eaton and Palisades fires claimed the lives of at least 28 people and burned more than 40,000 acres outside Los Angeles over the past three weeks, making them the most destructive fires in Southern California's history. With the Los Angeles burns still only partially contained, another pair of fires erupted last week outside San Diego, consuming about 6,000 acres and prompting evacuation orders.

As Californians take stock of the wreckage, thousands have lost their homes and businesses, and historically diverse and culturally rich neighborhoods were almost completely wiped out. Many will struggle to rebuild for an increasingly common reason: They didn't have adequate insurance.

Around 1,600 homeowner's insurance policies were dropped in the Pacific Palisades alone last summer, and thousands of homeowners in other fire-impacted communities like Altadena and Monte Nido also lost their policies over the past year. Some homeowners then opted for state-provided insurance at a much higher cost. Others who couldn't afford it chose to forego insurance entirely in hopes they'd never need it, but after the fires, sadly many of them did.

Their stories are only part of an insidious and growing insurance crisis across the United States that experts say is tied to climate change. Nearly 2 million homeowner's insurance policies have been dropped across the U.S. over the past seven years, or "non-renewed" in the language of the insurance industry, according to a congressional investigation released last month.

"The data confirm that it is climate change that is driving increasing non-renewal rates, as the counties that are most exposed to climate-related risks such as wildfires or hurricanes are the counties seeing the highest non-renewal rates," the Senate Budget Committee reported. As more companies back out of high-risk areas, the cost of insurance grew 40 percent faster than inflation from 2020 to 2023, the committee found.

"If you're not worried, you're not paying attention," California Sen. Bill Dodd told The Orange County Register in 2023 following a similar report released by the First Street Foundation, which predicted massive insurance price spikes as companies retreat from high-risk areas in California and other states including Louisiana and Florida.

What's driving the climate-fueled insurance crisis?

As global temperatures increase, extreme weather events such as droughts, flooding, and coastal storms become more frequent and intense. And this isn't just modeling or conjecture. It's already happening today. In the 1980s, the U.S. averaged about three extreme weather events per year with damages exceeding $1 billion. By the 2020s, the rate of billion-dollar disasters increased more than seven times. With an average 23 such events each year over the past five years, the collective cost reached nearly $750 billion, not to mention the human toll that comes with lives, homes and communities lost.

"We're seeing documented, clear statistical trends where climate disasters, and damages from those climate disasters, are increasing," said Jeremy Porter, head of climate implications research for the First Street Foundation, which quantifies climate risk for homes and businesses down to the property level. "Because of that, we're seeing increasing insurance payouts. Over the last five to 10 years in particular, the profit margins and the loss ratios for insurance companies have really kind of turned upside down. In a lot of cases, they are paying out more than they're bringing in year-over-year."

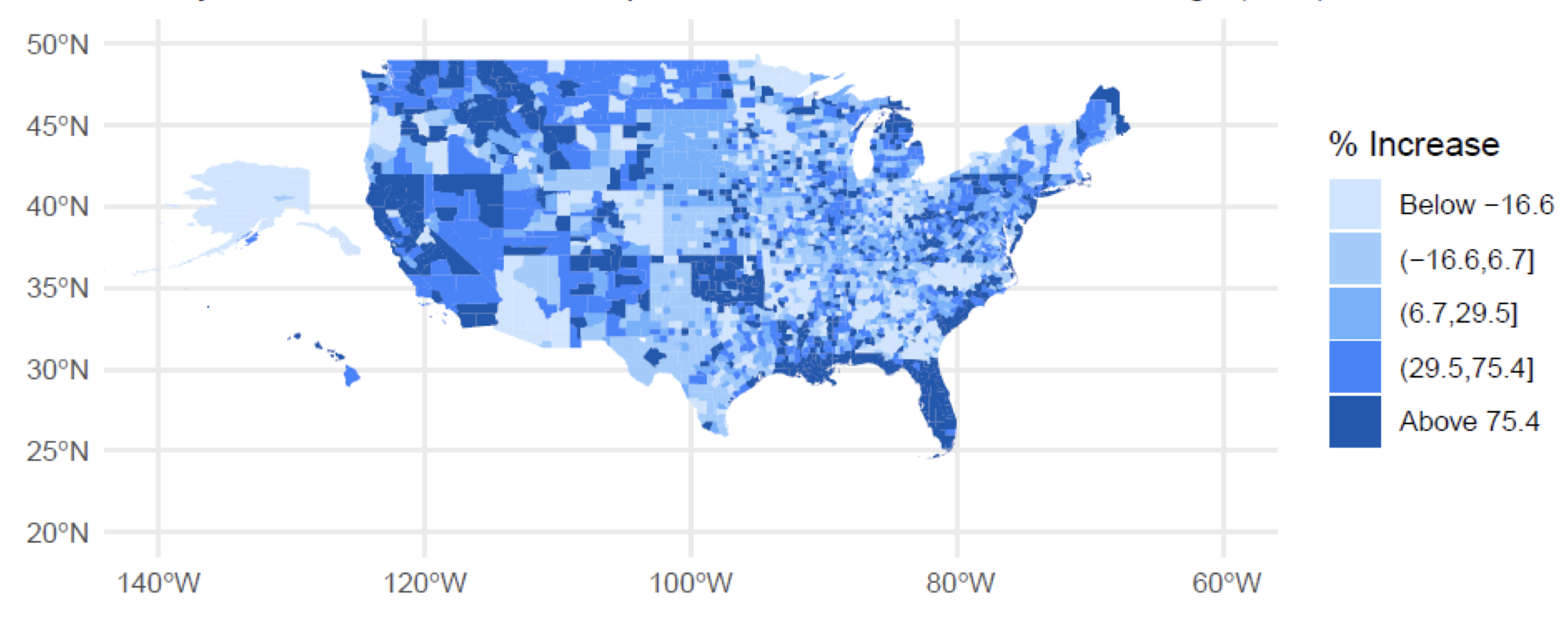

As a result, insurance companies are raising rates for homeowners to make up for their losses, and many have decided not to renew policies in high-risk areas. Some California counties have seen non-renewal rates increase by more than 500 percent since 2018, according to the Senate report. Non-renewals tripled in Hawaii over the same period due to rising risk of storms and wildfires, and communities across coastal South Carolina, Louisiana and Florida are seeing some of the highest rates of non-renewals in the country. But it isn't just coastal communities who are feeling the strain. Rising wildfire risk in parts of Wyoming and increased flooding in central Texas have also driven more non-renewals and higher premiums for homeowners.

When policies aren't renewed, homeowners are often forced into the residual insurance market made up of what's known as insurers of last resort. These state-supported programs are meant to fill gaps in the private insurance market, including in areas that insurance companies consider too high-risk to cover. "All homeowners, all businesses, all entities have some right to insurance of some sort," Porter said. "The problem is that those residual markets are often very expensive relative to the private market."

For example, policy premiums for California's insurer of last resort, the California FAIR Plan, are often three to four times higher than those in the private insurance market, he said.

From coast to coast, communities are feeling the strain

Other than the fact that extreme weather events are increasing in regions across the U.S. at a rate faster than insurers can keep up with the damages, the mounting insurance crisis often plays out differently in different states depending on regulations.

California, for example, puts a cap on insurance rate increases. "Anything that's above a 6.999 percent increase in the premium has to go before the insurance board and the insurance commissioner's office. Oftentimes it doesn't get approved," Porter said. "So, insurers will raise their rates at a max right up to that 7 percent limit year-over-year, but it's not keeping up." Since insurers can't increase prices, they're not renewing policies to avoid taking on what they see as untenable risk. As a result, the number of homeowners forced to obtain policies from the FAIR Plan after being dropped by their private insurer increased by 500 percent in 2020 alone, according to First Street's report.

Although Florida's cap on premium increases is higher than California's, the state still saw insurance prices rise more than 60 percent from 2019 to 2023. Florida's insurer of last resort, the Citizens Insurance Agency, is now the largest insurer in the state.

"It is remarkable to me that an insurance company that was set up just to provide a residual market for people who couldn't get insurance anywhere else is now the largest insurer," Porter said. "They hold so much risk in that company, and in those places, people are seeing such increases in insurance cost. Whether you can't get insurance in the private market or you can't afford it in the residual market, we are also seeing a troublesome trend of people starting to go without insurance and self-insuring."

Forgoing insurance is enormously risky, but many homeowners feel they have no choice. "It's particularly problematic in places like South Louisiana — where insurance has just spiked through the roof because of the risk in the area, but it's a working-class area with modestly priced homes," Porter said. "All of a sudden you have a $12,000 insurance policy on a $120,000 property. It's hard to sustain that for people in a lot of those communities."

What homeowners need to know to manage their risk

As a similar trend of non-renewed policies and rising prices takes hold in insurance markets across the country, people are being forced to grapple with a new cost of homeownership they were not expecting.

"There are a lot of different stories that we're hearing from folks. Maybe they feel kind of anecdotal, but a lot of them center around unknown risk," Porter said. "I met a gentleman from Texas who moved to Norfolk, Virginia, and we were in that community on a high-tide day. The water was halfway up his front yard, and half of his driveway was covered in water. He came out and he said, 'When I moved here, it was sunny, it was a nice day. We're not even that close to the water. There's no way I thought this property would flood. If I knew that, I would've never moved into this area.’"

How to tackle the challenge on a mass scale is a difficult question to answer. Some countries, such as Spain, use federal funds to compensate homeowners who face impacts from extreme weather. In the U.S., Porter said regulators could begin to change the landscape by allowing insurers to use forward-looking climate models to underwrite and price policies, rather than the backward-looking models that are used today. But it could come at the cost of more short-term strain for homeowners.

"California is just starting to pivot toward allowing climate models to be included in the pricing algorithms, which will loosen the regulations. While that will be more attractive to the insurance companies, so you'll probably see more private insurance companies move back into the market, it will raise rates significantly for homeowners," Porter said. "There's almost a market correction that has to happen for us to get to a place where we're pricing risk properly and everybody understands what risk looks like where they live."

Getting there, however, could be painful. "The biggest problem in that whole transition stage is that there are a lot of people who took out a 30-year mortgage 15 years ago," Porter continued. "They expected to pay a certain amount of principal, a certain amount of interest, a certain amount of taxes, and a certain amount of insurance. Now, their insurance has jumped four or five times what it was when they took out their mortgage. So, effectively their fixed-rate mortgage has become a variable-rate mortgage that only goes up, and they may not have bought this home if they thought that was going to be the cost of homeownership."

Being aware of the potential risks and the local insurance market can help those considering buying a home or property to protect themselves, he said. First Street publishes climate risk data for every property in the United States via a search in the top toolbar of its website, and this data can also be found in the property-level details section for homes listed on Zillow, Redfin, Realtor.com and Homes.com.

"The information is particularly useful in regard to understanding what climate hazards the property is at risk of being impacted by and what the cost of that risk is on an annualized basis, which when projected out into the future, can give property owners and buyers insight into how insurance will increase," Porter said. "Using this data, property owners and buyers can make climate-informed decisions around where to live, the affordability of the property, and the potential increases in ownership costs into the future."

Mary has reported on sustainability and social impact for over a decade and now serves as executive editor of TriplePundit. She is also the general manager of TriplePundit's Brand Studio, which has worked with dozens of organizations on sustainability storytelling, and VP of content for TriplePundit's parent company 3BL.