The Outer Banks vacation rentals business Twiddy & Company restored and relocated the historic Kill Devil Hills Lifesaving Station, which was used by volunteers responding to shipwrecks off the coast. It now serves as the company's real estate sales office in Corolla, North Carolina. (Image: Taylor Haelterman)

This story about employee housing in the Outer Banks is part of The Solutions Effect, a monthly newsletter covering the best of solutions journalism in the sustainability and social impact space. If you aren't already getting this newsletter, you can sign up here.

From the Wright Brothers to the notorious pirate Blackbeard, North Carolina’s Outer Banks is steeped in history. Much of this 200-mile stretch of islands was preserved as the first national seashore in the United States. Its newsworthy events and scenery slowly attracted tourists who, until the mid-1900s, traversed through the sand dunes and forests on makeshift trails.

Vacation rentals are the lifeblood of the local tourism industry. The Outer Banks hosts thousands of them alongside very few hotels. That’s at least partially because the islands are actually shifting sandbars with no bedrock to anchor them down, slowly but constantly eroding and changing shape. These narrow strips of ever-moving sand can’t support the water and sewer infrastructure necessary for large hotels.

“The Outer Banks is unique in one way because it was almost custom-built for a vacation home market,” said Clark Twiddy, president of the local vacation rental home business Twiddy & Company. “We didn't have the infrastructure to support hotels. The infrastructure there that you typically see is a result of a centralized planning process. We didn't have that, so we kind of did it ad hoc.”

His father, Doug Twiddy, opened the company’s first headquarters in a small town called Duck in Dare County in 1978 and a second one in the Outer Banks’ northernmost town, Corolla, a few years later.

“I grew up on the Outer Banks, and we had an opportunity to watch the Outer Banks grow,” Twiddy said. “There were seven kids in Duck. Three of them were me, my brother and my sister. So it was a very different place.”

Since then, Twiddy & Company expanded to 1,000 vacation rental homes, employing 135 people full-time and over 300 during the summer tourism season. Almost all of them live on the Outer Banks or in the surrounding area.

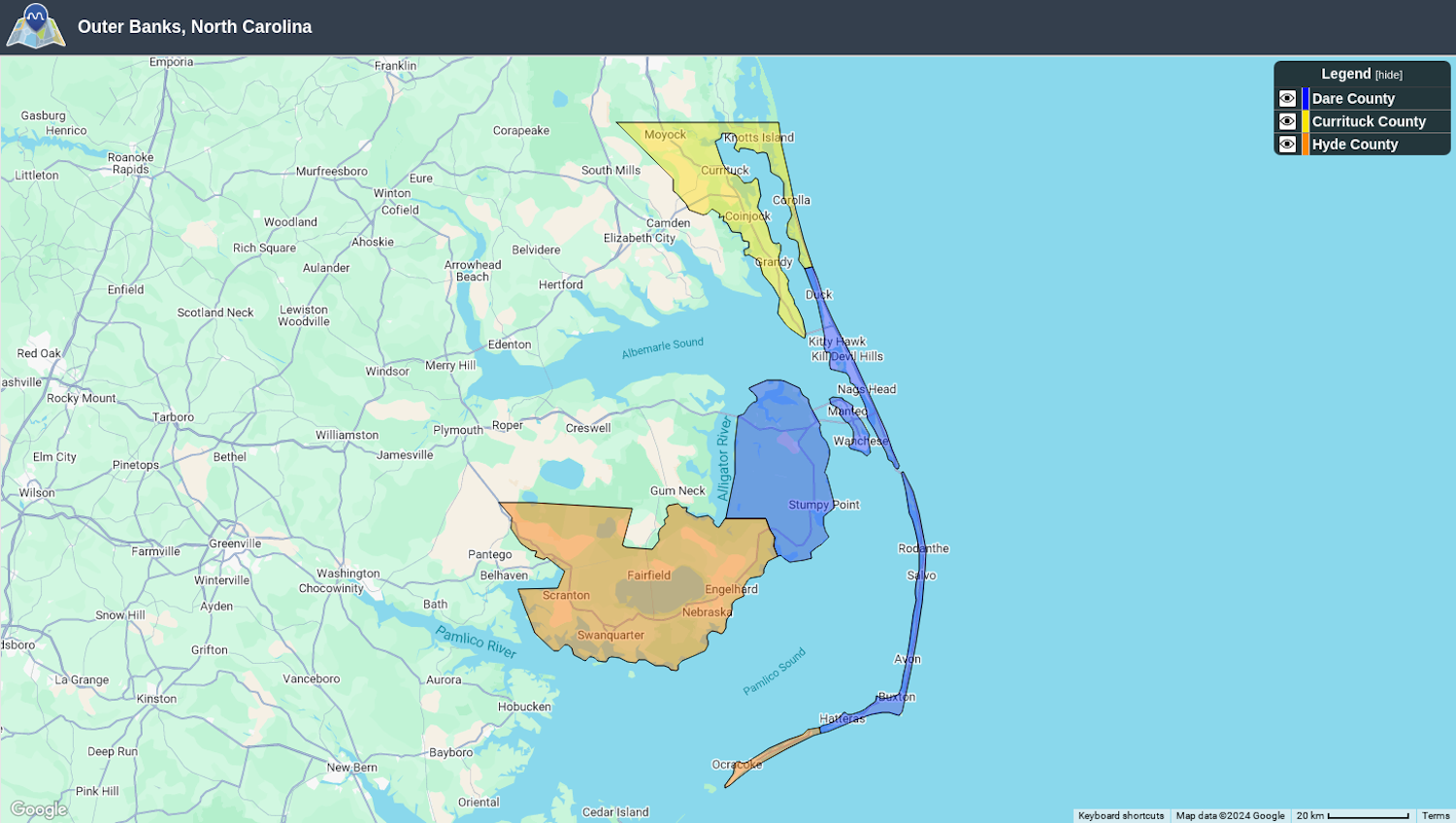

But this design, combined with a recent surge in tourism, has serious downsides. The three counties that span the Outer Banks — Dare, Currituck and Hyde — reported almost $2.8 billion in combined visitor spending in 2023, according to the most recent data available from the state’s tourism department.

In Dare, the largest of the three counties with a population of about 38,000, over 45 percent of local jobs are related to tourism, according to the county visitors bureau. Currituck, the second largest county, reports over 2,400 jobs stemming directly from travel and tourism businesses, according to the most recent data available from 2022.

As tourism rises, the industry that the local economy depends on is pushing out the residents who make it possible. As more homes are turned into lucrative short-term vacation rentals, it gets harder to find affordable long-term housing, forcing workers to move away and leaving businesses severely understaffed. With stretches of the islands reaching just a few miles or less in width and beach erosion already causing homes to fall into the ocean, simply building more isn’t the answer.

When visitation peaked during the pandemic, “They were getting [workers] in from hours, sometimes two hours away to come and clean rooms and turn over houses and all of that,” said Whitney Knollenberg, associate professor and extension department specialist in tourism at North Carolina State University. “We were really starting to see these negative impacts.”

It’s a problem that those who laid the foundation for this incredible growth never saw coming.

“I chatted with a gentleman who was probably 90, and I said, ‘Why? Why didn't you guys plan for this?” Twiddy said. “He said, ‘We had no idea … This, and what the Outer Banks has become, was beyond our wildest imagination. We would've been less surprised if aliens had come down and landed than we are to see what the Outer Banks has become. We simply couldn't have imagined it.’ Which is a telling story as we think about planning for future growth.”

Hoping to support that planning process, Twiddy & Company worked with the North Carolina State College of Natural Resources and Knollenberg to launch the Lighthouse Fund for Sustainable Tourism in 2021. She spent two months speaking with residents, business owners, workers, elected officials, and other locals to learn more about how to solve the tourism-related problems they face. Among other things, her initial findings primarily echoed the grave need for affordable housing.

“We don't have people to work in the industry,” she said. “We don't have affordable housing for them to live in these communities. We have very high peak levels of tourism, and then there's nothing in the off-season. Our stakeholders feel like this is happening to them, and that they're not a part of this process.”

While the communities build long-term plans to sustain the tourism industry and future growth, businesses across the Outer Banks are buying homes to offer subsidized housing for their employees. “Any business you visit that's a service business on the Outer Banks — restaurant, retail, real estate — owns its own housing, or they're not in business,” Twiddy said.

That includes Twiddy & Company. “We have made capital investments in housing our staff and their families,” Twiddy said. “Huge investments and surprising levels. I won't disclose the number, but to any business anywhere in the world, those would be considered capital investments … We include housing in that because we also recognize that without housing, we don't get talented people and smart people, because it's unaffordable.”

Though buying up property to turn into short-term rentals provides a bigger monetary return on investment, businesses in the Outer Banks have a different incentive. They’re investing in their employees' creative and cognitive contributions to the business, which essentially offsets the subsidized price of rent, Twiddy said.

“That's how businesses can justify, although it's not an insignificant expense,” he said. “If you go to a restaurant and you say, ‘Why is this food so daggone expensive?’ Because they have to pay rent, or they have to pay a mortgage for the house that they have their wonderful team in.”

It’s part of an approach Twiddy calls the “Iron Triangle,” which emphasizes the importance of sending money back into the community to support local healthcare, housing and education. He credits the approach as part of the reason the rental company built and sustains such a large local workforce.

“If we are to be this local organization that is an ambassador of what this destination could be, we believe very deeply that we have to be participants in it. We send our kids to school here. Many of us will be buried here,” Twiddy said. “We have to accept, first and foremost, the responsibility of the economic growth we have helped create. I believe it's been overwhelmingly positive, as somebody who grew up here when there were seven kids … But there can be detrimental impacts. We have to be responsible for both. And if we accept that responsibility, we have to have a corresponding obligation, I believe, to do the things necessary to mitigate those impacts and support our community as much as we can.”

One of Twiddy & Company’s offices is situated in Corolla. As the northernmost town on the Outer Banks, it is only accessible by one road, has a permanent population of about 500 and is slammed with hundreds of thousands of visitors during the summer. Alongside affordable housing, Corolla once lacked a school. In 2012, the rental company reopened a historic one-room schoolhouse it had previously used as an office and educational exhibit as a charter school for the town’s youth. It’s another example of the Iron Triangle philosophy at work.

“That's the only school in the northern Outer Banks,” Twiddy said. “The other schools are all on the mainland, which is well over an hour car ride. This allowed us to bring families back in terms of employers, employees, a lot of the community in Corolla.”

Now, the schoolhouse is packed, and it’s time to expand. Twiddy & Company donated a plot of land for a new school building to be built. “Think about how many more families that attracts to an area that before didn't have that opportunity — that couldn't live here,” Twiddy said. “This will overwhelmingly be funded directly or indirectly by tourism.”

As beneficial as they can be, these investments can have negative impacts, too. When the rental company bought its first batch of employee housing, Twiddy expected young people to move in, save enough money for a down payment on their own home and move out. But now, down payments are much bigger, and what was envisioned as a short stopover became a decade-long stay with unintended consequences.

“That keeps those folks there. It also has the impression of tying their work to their house,” Twiddy said. “You and I would say, ‘Look, we can't quit because if we quit, we lose our house.’ We never wanted that. So in hindsight, there were some things we'd have done about it differently.”

On top of that, businesses buying up the cheaper homes on the market is compounding the housing problem, driving up prices and freezing out people who don’t work at those businesses, Twiddy said.

“Now any home on the Outer Banks that hits the market at less than $500,000 gets bought and goes into contract the same day, not by someone who wants to live there full time, but by business,” he said. “You have this whole community of people in the Outer Banks who are tied to their job because it's their house. And in fairness, nobody wants that.”

But for now, ensuring they have a place to stay is one of the only ways businesses can retain their employees. Though planning for a more sustainable future is beginning across the islands, many people are fearful of and resistant to the change required to solve these problems, Twiddy said. Paving a new way forward will require addressing those fears and more collaboration across county lines and opinions.

Knollenberg agreed. “One of my short-term recommendations, which I'd really like to tackle, is to create space for stakeholders to contribute to and prioritize actions for destination management,” she said. “There needs to be more of this communication, more of this space for our tourism decision makers to hear from those people who are impacted.”

There’s room for a stronger region-wide approach to solving tourism-related issues, too, Knollenberg said. No structure exists for that, and building one will take someone stepping up to champion the effort and sustained support. She wants to start with connecting the Outer Banks with other leaders and communities acting on similar issues in the future.

“Not everybody agrees on housing,” Twiddy said. “There are people in the Outer Banks who, like me, think tourism is overwhelmingly good and the offsets are relatively small. I could introduce you to people in 10 minutes who would feel the opposite, so there's no consensus there. It's our ability to compromise that's really on the line.”

Taylor’s work spans print, podcasts, photography and radio. She brings her passion for covering social and environmental issues through the lens of solutions journalism to her work as assistant editor.