(Image: Zac Wolff/Unsplash)

The U.S. wind industry often faces criticism for failing to recycle decommissioned wind turbine blades. Thousands of these massive pieces of equipment are piling up in disposal sites across the country, and there are many more to come. That is a bad look for an industry that deploys sustainable energy as a selling point. Fortunately, new tools are emerging to help the industry build more circularity into its green profile.

Solving the turbine blade riddle before the numbers add up

Wind turbine blades are relatively new to the waste disposal and recycling streams, but their numbers are set to rise rapidly in the coming years. About 90 percent of U.S. wind turbines were installed after 2012, according the U.S. Department of Energy. Assuming a 20-year lifespan for a typical wind turbine, that adds up to an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 blades to be disposed of each year between 2025 and 2040.

The Energy Department’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) took a look at the situation in 2022 and warned of a significant gap between the nation’s current blade recycling resources and the number of blades to be recycled in the future. Among other issues, the massive size and weight of decommissioned blades make it expensive to transport them to a recycling facility, NREL noted. Disposal in the nearest landfill is a more economical alternative, though not necessarily a more sustainable one.

The NREL team estimated that up to 78 percent of decommissioned blades will end up in landfills under a business-as-usual scenario. That estimate is supported by studies showing that turbine blades account for a small fraction of the global waste stream. One study published in 2021, for example, found that turbine blades will take up just 1 percent of available landfill space by 2050. In other words, the raw numbers suggest that landfilling turbine blades is not a particularly significant waste disposal issue.

Nevertheless, the U.S. wind industry has a strong reputational motive to adopt recycling over landfilling. In addition, a growing number of farmers and other businesses are deploying their own wind turbines on-site to support their sustainability goals, a movement supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. These hyper-local renewable energy stakeholders form another constituency with an interest in finding more holistic alternatives to landfilling.

Near-term solutions for turbine blade recycling

Unlike other parts of a wind turbine, blade materials can’t be separated from each for recycling. Because they need to be strong, durable and lightweight, turbine blades are made from advanced composite materials containing glass, carbon fibers and epoxy binders.

“Blades are designed to last a long time, and the fundamental nature of a composite is you are combining dissimilar materials together that are not designed to come apart,” Patrick Sullivan, a strategy director at Owens Corning, which manufactures glass fibers that are used in the composite materials for wind turbine blades, told TriplePundit last year.

As one indicator of progress, last month the Energy Department announced six winners in its Wind Turbine Materials Recycling Prize program. Drawn from an initial cohort of 20 teams selected in January, the winners were judged according to their potential for advancing from the prototype stage to demonstration-scale systems and eventual commercialization.

One of the winners, the Iowa firm Critical Materials Recycling, is developing a more environmentally-friendly approach to retrieving the magnets used in various parts of a wind turbine. The other five winners focus specifically on blade recycling.

Among those five is the Cimentaire project in Houston, Texas, which makes a protective waterproof coating for concrete out of ground-up turbine blades. Another Texas company, United Standard Materials Corp., deploys a process called flash composite recycling to convert fiber-reinforced composites into the widely used compound silicon carbide. Among other uses, the compound can be used to improve the durability of new turbine blades. The flash composite system also produces hydrogen as a byproduct, which can be deployed in fuel cells, fertilizer production, and other industrial systems.

Shredding turbine blades is another commercially promising strategy recognized by the Energy Department. In that area, the West Virginia firm Fletcher Engineered Solutions is developing transportable equipment that can shred an entire blade on-site, without the time and expense of cutting it into sections beforehand. Similarly, GreenTex Solutions of South Carolina is developing an on-site shredder with the aim of using the material to produce flooring panels, which can also be recycled when their lifespan is over.

A third winner in the shredding space is the Wind Rewind project at the University of Maine, which plans to use shredded wind turbine blade material as a low-cost additive to plastic used in large-scale 3D printing.

The “limitless” wind turbine blade of the future

The six finalists each earned a $500,000 cash prize along with technical support to help them take the next steps toward demonstration, validation and commercialization.

In the meantime, the Energy Department also supports research aimed at encouraging the wind industry to adopt new materials that allow for turbine blades to be reused, rather than granulated or shredded. The challenge is to reassure the wind industry that the new materials perform as well, or better than, conventional turbine blade materials.

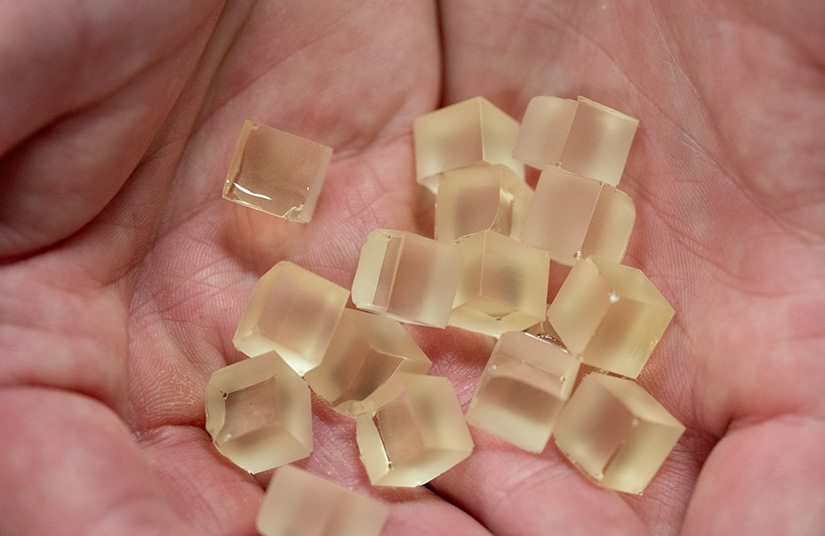

One significant area of focus is the resin used to bind turbine blade materials together. In August, NREL announced a milestone study in the development of a new bio-based resin. The new resin enables recyclers to deploy a low-impact chemical process that dis-assembles turbine blades into their component materials. The materials are intact and can be reused multiple times.

“It is truly a limitless approach if it’s done right,” Ryan Clarke, a postdoctoral researcher at NREL and lead author of the new study, said in a statement. His team found the bio-based resin to perform "on par" or better than those in use today.

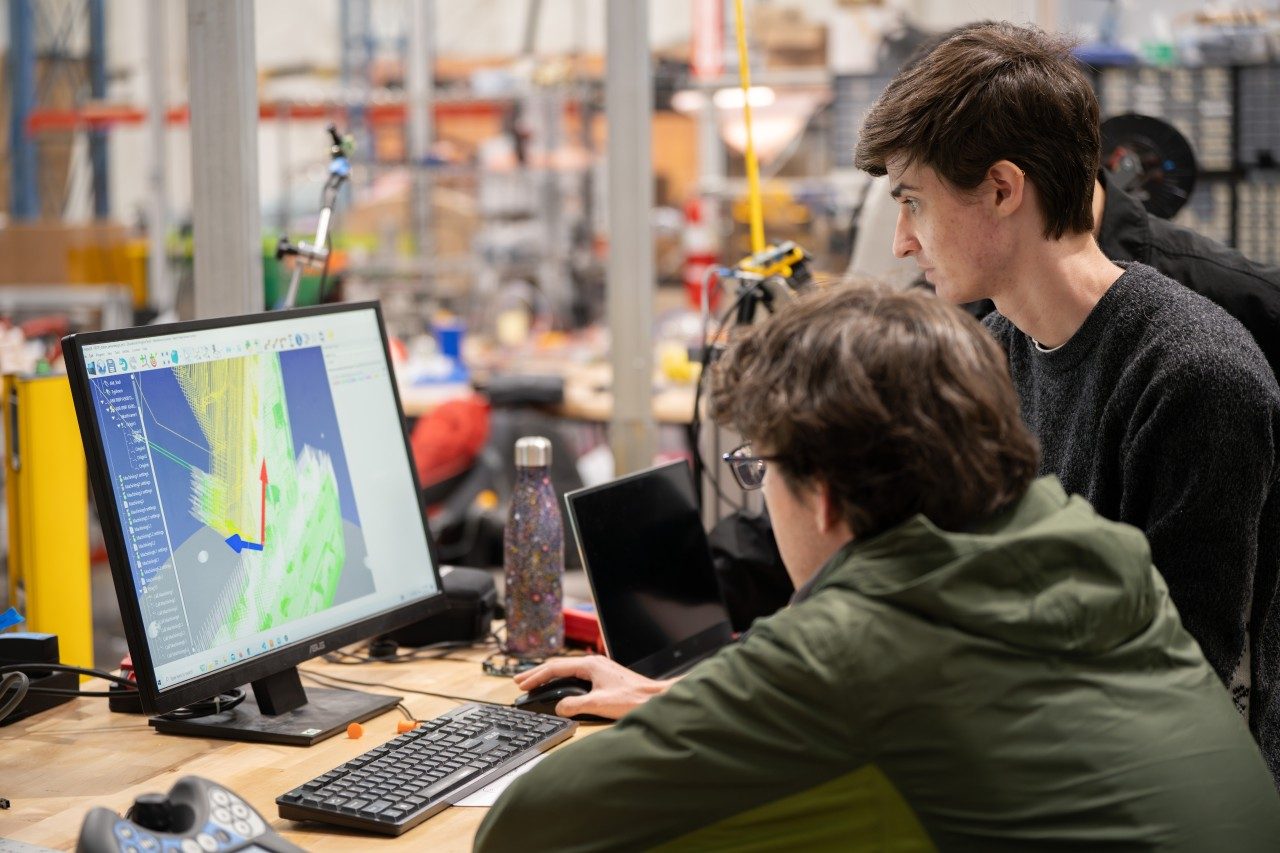

A similar project is underway at Virginia Tech. Funded in part by the Energy Department, the Virginia Tech team is working on an ambitious turbine blade manufacturing method that combines large-scale 3D printing and high-performance design with a new, fully recyclable polymer composite. The process eliminates the use of hazardous materials, enabling the composite to be reprocessed into new blades.

As an additional benefit, the Virginia Tech team aims to manufacture turbine blades at or near the site of installation, avoiding the considerable cost of transporting whole blades from a distant factory.

Zooming out to see the big picture, the environmental issues confronting the wind industry are pea-sized compared to the boiling stew of disaster brewed up by the fossil energy industry over the last century. Still, wind stakeholders can — and should — set their own bar for progress and take advantage of a more circular, sustainable way to manage end-of-life for turbine blades.

Tina writes frequently for TriplePundit and other websites, with a focus on military, government and corporate sustainability, clean tech research and emerging energy technologies. She is a former Deputy Director of Public Affairs of the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, and author of books and articles on recycling and other conservation themes.