The Water Security Compass provides a more accurate picture of water scarcity by integrating human interventions into its assessments, which is useful for areas like the Colorado River, where infrastructure like the Hoover Dam needs to be accounted for. (Image: Christian Lendl/Unsplash)

Climate change is altering the world’s water cycle in ways that profoundly impact ecosystems, agriculture, industry and communities. Higher evaporation rates from increased temperatures lead to moisture accumulating in the atmosphere more quickly, which causes intense rainfall events that can lead to flooding. This great redistribution of global precipitation also causes more frequent and intense droughts in other areas.

A change in the timing and distribution of rainfall events disrupts agricultural cycles and human water supply, leaving companies, governments, and individuals in need of reliable data to better manage water resources.

The Water Security Compass is a first-of-its-kind online tool that aims to address a critical data gap in global water management: understanding the interplay between natural hydrological processes and human interventions. It was developed collaboratively by the consumer packaged goods company Suntory Holdings, the engineering consulting company Nippon Koei and the University of Tokyo’s School of Engineering.

“Monsoon regions in Asia, home to over 50 percent of the world’s population, receive the highest annual rainfall in the world, but they face large seasonal fluctuations in water resources,” said Harumichi Seta, senior general manager and biodiversity and water stewardship lead at Suntory Holdings. "In assessing the balance between supply and demand, it is vital to include infrastructure.”

The tool helps show the reasons behind the risks. “When we talk about water risk it is about how much water we need,” said Daikichi Ogawada, deputy general manager of the Center for Advanced Research at Nippon Koei. “That’s a question about human activity. We can use the compass to show human water demand, environmental requirements, domestic requirements, industrial and more.”

The tool driving the Water Security Compass is H08, a water resource model developed by Naota Hanasaki, a hydrologist and visiting professor at the University of Tokyo’s School of Engineering. Unlike other tools, H08 integrates human interventions into water assessments, providing a more accurate picture of water scarcity.

“Other models often overestimate water risks because they fail to consider the mitigating effects of infrastructure,” Hanasaki said.

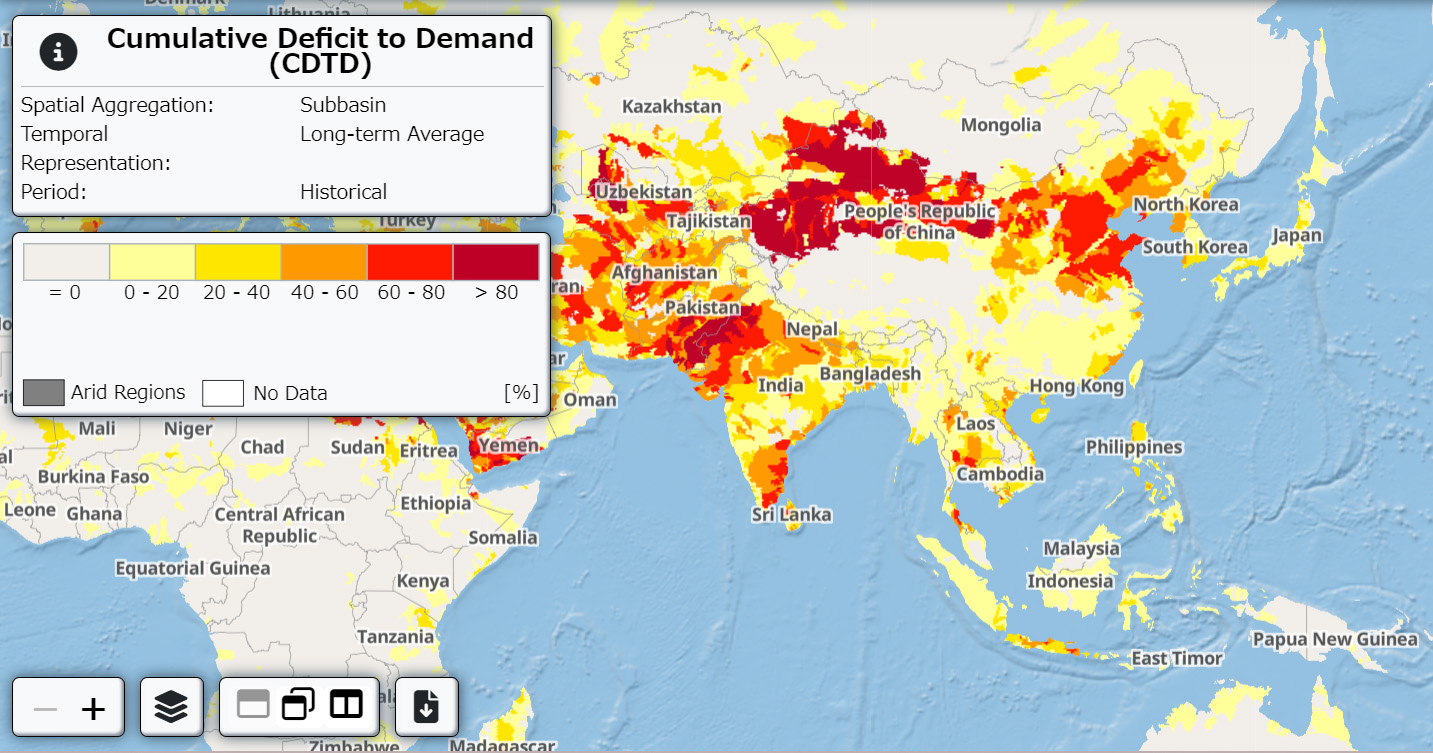

The Water Security Compass uses information that reflects both natural and human-modified water cycles, such as areas where human demand outstrips supply. It also differentiates water stress across agricultural, industrial and household uses.

“Without accounting for infrastructure, 17 percent of the world’s population would live in highly water-vulnerable areas,” Seta said. “With infrastructure factored in, that figure drops to 11 percent.”

The Water Security Compass’s ability to incorporate these nuances makes it particularly valuable for regions like India, where conventional models show extreme water stress but fail to account for infrastructure’s role in alleviating agricultural water shortages. Or areas along the Colorado River, which would experience severe flooding in the summer without dams.

The tool is not only focused on current water shortages, it also simulates future water risks under various climate scenarios. Users can input data like temperature changes, water demand by sector, and environmental requirements to visualize potential deficits decades into the future. These projections are color-coded on interactive maps.

“The core concept is to induce action and initiative from users,” Seta said. “The tool helps users visualize issues within each watershed and formulate strategies based on these scenarios.”

Users can have a more comprehensive view of water scarcity risks when data on infrastructure, seasonal changes and projected climate impacts are combined, Seta said. The Compass also highlights opportunities for nature-based solutions and green infrastructure, which can help address water issues. “Before, users could see where water stress existed but didn’t know what actions to take,” Seta said.

As with any new technology, the Water Security Compass faces challenges. Data gathering remains a hurdle, particularly for regions with limited monitoring infrastructure. “While we strive for precision, there are uncertainties,” Hanasaki said. “River discharge simulations may not always match observations perfectly.”

Despite that, the team is confident in the tool’s ability to provide a robust foundation for decision-making. “What surprised us most was the clear contrast in water risks with and without infrastructure,” Hanasaki said. “This simulation is incredibly advanced, even for hydrologists, and highlights the significant impact of human interventions.”

Looking ahead, the developers aim to refine the tool further before launching it in full in 2025. The creators hope it will drive greater industry-academia collaboration and support the development of comprehensive water conservation strategies worldwide.

“The point of the Water Security Compass is to show the direction — where is the best way to go?” Seta said. “Our hope is that users will understand their situation, set their strategy and take action.”

Mary Riddle is the director of sustainability consulting services for Obata. As a former farmer and farm educator, she is passionate about regenerative agriculture and sustainable food systems. She is currently based in Florence, Italy.