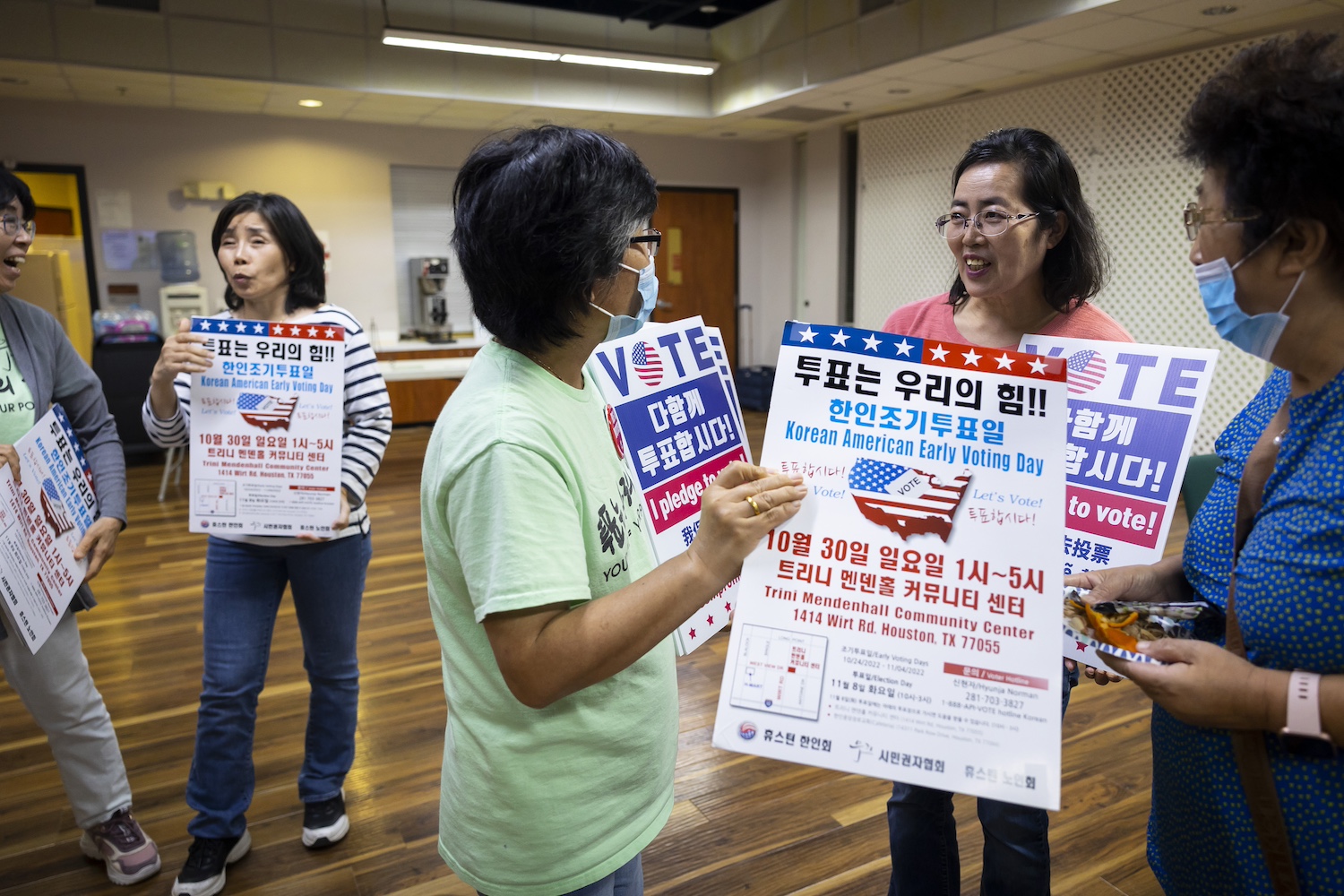

(Image courtesy of Woori Juntos.)

Natural disasters are terrifying enough in their own right. Imagine being unable to understand warnings, directions, emergency declarations, or how to access post-disaster relief because the information is broadcast in a langue you aren’t proficient in. That’s the reality for many immigrants and refugees, and it’s more than just an inconvenience. Lack of language inclusivity puts lives at risk.

While there are laws requiring language accessibility where federal funding is concerned, enforcement is lax. When speakers of a specific language make up less than 5 percent of the total population in the area, those laws might not apply anyway. Compounded with systems that create challenges to accessing emergency information in various languages, immigrants are often left in the dark — literally.

“Some people were in the dark, were in the heat, and didn’t have access to get to the cooling center, and didn’t have access to call us and let us know that they needed help,” Quỳnh-Hương Nguyễn, the senior communication associate at Woori Juntos said, referring to a deadly storm that swept through Houston, Texas, in May. Similarly, emergency notifications for a chemical fire in the city last year were only sent out in English and some Spanish, leaving many without proper warnings or instructions.

Woori Juntos aims to address these issues by empowering the Asian, immigrant and migrant communities in Houston. The organization focuses on helping them navigate local services and organize to advocate for policy.

Jumping through hoops for language access

“No one was informed about it,” Nguyễn said of the recent storm. “It was only afterwards where people were getting information … like, ‘There's a few cooling centers, there's a place to charge, there's a place to get to get rid of tree debris.’ Now the problem with that, again, is it’s all English focused. So if you are a Korean member or a Spanish-speaking member, and let's say this big tree is in your house right now, how do you get that [removed]?”

Instead of automatically supplying emergency notifications and recovery information in all relevant languages for an area, English is often the default. In Houston specifically, community members have to sign up for alerts online, and that form is also in English, Nguyễn said. This creates a huge barrier for people who are not tech-savvy, especially the elderly, who are the most vulnerable in emergencies.

Further complicating emergency response — whether it be due to a natural disaster or personal health crisis — first responders don’t speak many of the languages present in the community. As a result, many immigrants struggle to get the help and treatment they need from police and medical professionals, Nguyễn said. This leaves organizations like Woori Juntos scrambling to help with translation and access to services to keep community members who would otherwise slip through the cracks safe during emergencies.

Bridging the language gaps

Woori Juntos means “we rise together” in a combination of Korean and Spanish. The organization works primarily with Korean, Vietnamese and Spanish-speaking immigrants, many of whom are from Central America. But it also works with smaller immigrant groups such as those from Laos and Cambodia. The organization doesn’t turn anyone away for language reasons and works with interpreters to bridge any gaps.

“On the service side, we focus mainly on helping a lot of our Korean elders, or Korean folks in general, to navigate a lot of the public system if they do not have a relative who can speak proficient English,” Nguyễn said. This includes navigating health care, citizenship, financial resources, disaster recovery and emergencies.

During the storm in May, for example, Woori Juntos immediately pivoted to a rapid response situation to ensure members could safely get to cooling centers in blackout conditions without access to public transportation, Nguyễn said. This is expected to be a regular part of Woori Juntos’ operation.

“We know that this is going to keep happening every year,” Nguyễn said. “I hate to break it to everybody I'm so sorry. But climate change is so real.”

The climate crisis is a big part of Woori Juntos’ organizing and policy work, with members listing it as one of their biggest concerns in addition to language access and community safety. The organization uses its translation services to assist members in testifying at the city council and the state capitol.

“Our programming is very language accessible driven,” Nguyễn said. “Meaning that when it comes to our civic engagement, our social navigation programs and policies, we make sure that it is in their language.”

Building trust

That doesn’t mean it’s necessarily easy to connect with all of the immigrant communities in Houston. Outreach and notifications have to be tailored to the different immigrant groups, both culturally and language-wise.

Khmer people from Cambodia and Laotians have different ways of connecting, for example, Nguyễn said. Members of these communities were often hurt by the system, which means it takes a lot of work to build their trust.

“They are very protective of their people, especially when it's small,” Nguyễn said. This means staff often have to connect with trusted members of the community first and collaborate with them to reach others.

Making the most of limited funding

One of the biggest challenges facing immigrant organizations like Woori Juntos is funding, which comes from a combination of grants and private donations.

Only 0.2 percent of all the funding awarded as grants in the U.S. is designated for work in Asian American and Pacific Islander communities, according to a report by the membership organization Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Philanthropy.

While Woori Juntos doesn’t turn anyone seeking assistance away, the organization has had connect Central American immigrants with other organizations because it doesn’t have the capacity to help everyone who needs it. The people the organization serves come to the U.S. for a variety of issues — from chasing the American dream to fleeing climate disasters, poverty, and government collapse or abuse — and it’s likely that immigrant groups will continue to grow as the climate crisis worsens and governments struggle to deal with the repercussions. This will only increase the need for groups like Woori Juntos. Whether these organizations will be able to meet the needs of incoming refugees and immigrants will ultimately depend on funding.

Riya Anne Polcastro is an author, photographer and adventurer based out of Baja California Sur, México. She enjoys writing just about anything, from gritty fiction to business and environmental issues. She is especially interested in how sustainability can be harnessed to encourage economic and environmental equity between the Global South and North. One day she hopes to travel the world with nothing but a backpack and her trusty laptop.