Corolla, a community in the northern Outer Banks, bordered by the Currituck Sound on one side and the Atlantic Ocean on the other. (Image: Taylor Haelterman)

Like most tourism destinations, North Carolina’s Outer Banks spent decades trying to attract as many visitors as possible. While more and more people flock to its beautiful beaches, historical sites, and thousands of vacation homes, locals question if the advertising was too successful.

“For years and years and years, the tourism industry as a whole was really, really focused on marketing,” said Whitney Knollenberg, associate professor and extension department specialist in tourism at North Carolina State University. “The paradigm that the industry followed was ‘heads and beds.’ That means we want to get as many people into hotel rooms for as many nights as possible, because that is what is going to generate the economic impact that we want from tourism.”

In the Outer Banks, the growing industry needs to find ways to adapt to serious environmental impacts to sustain the level of tourism it built. The natural shifting of the sandbars these communities were constructed on is causing homes to fall into the ocean and doubling the length of ferry rides to southernmost Ocracoke Island, which can only be reached by boat, Knollenberg said. Like many coastal communities, the Outer Banks also face fallout from increasingly frequent and severe weather events. The barrier islands were dealt serious damage by severe flooding and high winds from Hurricanes Hermine and Matthew in 2016, Tropical Storm Michael in 2018, and Hurricane Dorian a year later.

Along with adapting to the natural world, the industry has impacts of its own. The wild horse herd that calls the northern beaches of Currituck County home has dwindled from thousands to around 100 horses due to habitat loss and deadly run-ins with humans. Increased visitors also means increased energy demand, water use and consumption, which come with their own environmental consequences and feed into the larger impacts the islands are already trying to manage.

Meanwhile, local workers find themselves pushed out by the very industry that employs them. It’s difficult to find affordable housing, and when workers leave, local businesses become too short-staffed to stay open.

The search for solutions led the North Carolina State College of Natural Resources to team up with Twiddy and Company, a family-owned vacation rental business in the Outer Banks, to launch the Lighthouse Fund for Sustainable Tourism in 2021. The fund supported Knollenberg’s research on sustainable tourism development in the Outer Banks. She stayed on the islands for two months that summer, having over 40 conversations with residents, business owners, workers, elected officials, and other stakeholders to learn more about the tourism-related challenges they faced and what the region can do to address them.

From destination marketing to destination management

Destination marketing organizations, like visitors bureaus, are typically funded by the occupancy taxes travelers pay when they stay in hotel rooms, which can be anywhere from 6 percent to 17 percent, Knollenberg said. They’re incentivized to keep following the same model because the more heads and beds they get, the bigger their budget.

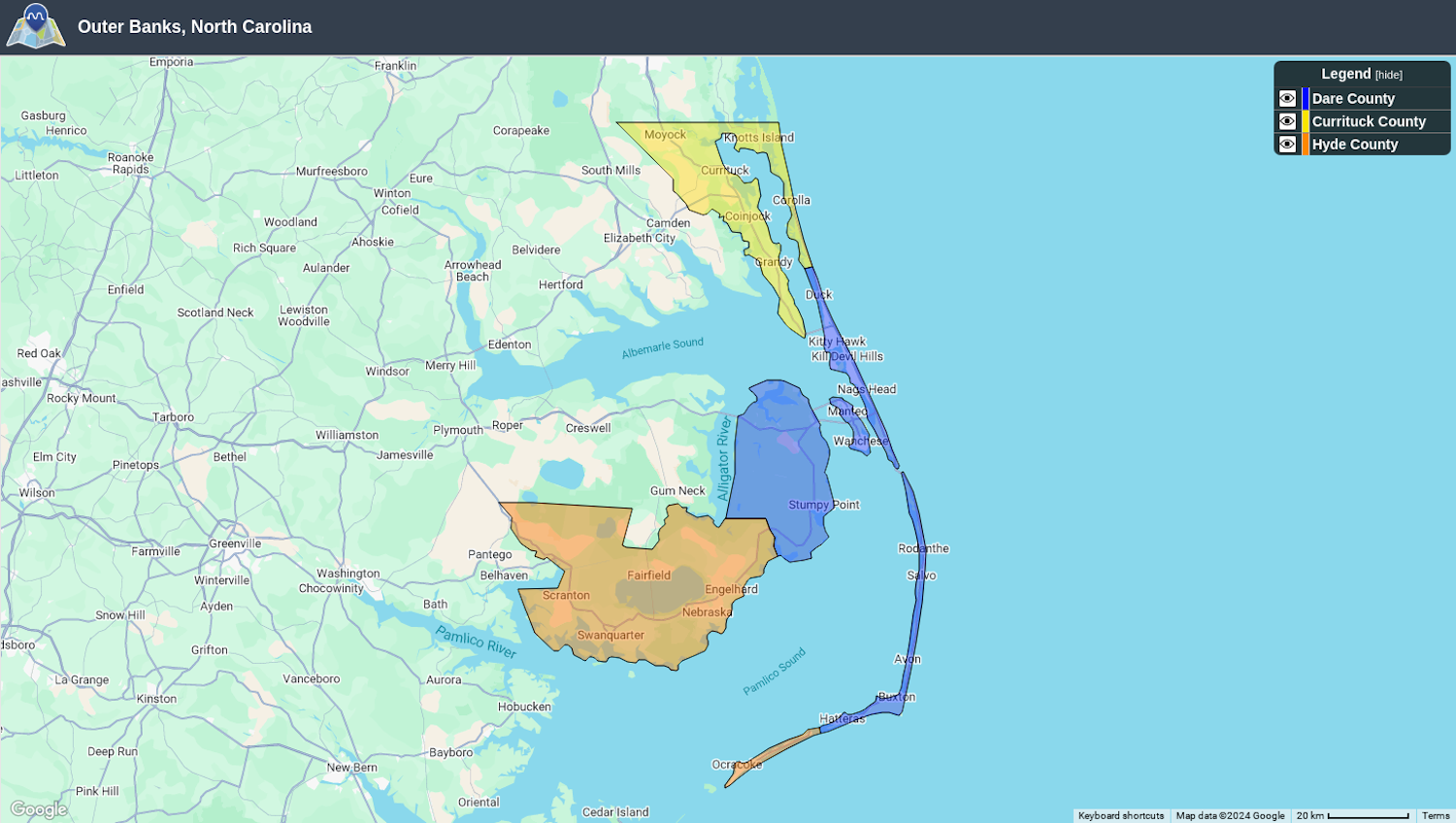

Dare, Currituck and Hyde counties, which make up the 200-mile chain of barrier islands known as the Outer Banks, saw combined visitor spending of almost $2.8 billion in 2023.

Visitation has exploded since the COVID-19 pandemic. Dare County alone reported a 40 percent increase in visitor occupancy at the end of the peak tourism season in September 2020 compared to a year earlier and marked another increase of almost 15 percent the following year.

“We are at insane levels of occupancy. I'm talking in 2021, they were at 97, 98 percent occupancy,” Knollenberg said. “Which means even if you wanted to come to the Outer Banks, you couldn't because there's no place for you to stay.”

Occupancy numbers in Dare County leveled out after that, then decreased by nearly 12 percent this year. But the county is still seeing hundreds of thousands more visitors than in the years before the pandemic. That trend continues across county lines.

“What happens oftentimes is they do a really good job, and they get a lot of people to come, and they get a lot of heads and beds. Now we're starting to see the consequences of that,” she said. “We really succeeded in getting people here. Now what do we do?”

One of the recommendations from Knollenberg’s research is to move away from the industry norm of destination marketing, replacing it with destination management.

“That is happening in the industry worldwide at this point,” Knollenberg said. “We're starting to say, ‘Okay, we're no longer destination marketing organizations. We're destination management organizations.’ It's not about this paradigm of heads and beds. It's more about: How do we make sure tourism does the most good for our community that we can? And you're starting to see that change.”

“It should happen with the community”

Dare County started considering this shift when the Outer Banks was overwhelmed with visitors during the pandemic. The county’s visitors bureau, named the Outer Banks Visitors Bureau, created a Long Range Tourism Management Plan that aligns with this idea of destination management.

“That whole process kind of fundamentally changed the way we go about our business,” said Lee Nettles, executive director of the bureau. “Visitors bureaus like ours, destination marketing organizations, have traditionally been all about demand generation. You couldn't help but notice that something had to change, that more was not better, more was not the answer.”

Released in 2023, the plan was informed by over 4,500 responses from locals during town hall meetings and through surveys, Nettles said.

“It's kind of terrifying, as the director of the tourism promotion entity, to put a survey out there, but it was really constructive,” Nettles said. “The consultant said it was far and away their largest response. And we're a small community. We're only 38,000 or so people … It said to us that the people who live here, obviously, care greatly about the place. But also, I don't think you respond to something like that unless you believe things can change and your input can make a difference.”

The plan calls for creating a dedicated task force to curate the input of thousands of residents and tourism community stakeholders.

“Tourism is something that shouldn't happen to a community,” Nettles said. “It should happen with a community.”

As organizations shift from destination marketing to destination management, Knollenberg recommends they create a staff position dedicated to advancing sustainable tourism and working with the community.

Dare County created a similar position alongside the new tourism management plan called the director of community engagement, who is tasked with bringing the plan to life, Nettles said. They work with a committee of 22 people from across the Outer Banks — think: residents and representatives from local institutions like hospitals and schools — to figure out the best ways to tackle the goals in the plan and coordinate efforts with community groups.

And the bureau isn’t leaving tourists out of the work. One of the key goals of the management plan is to strengthen resident and visitor engagement and keep the gap between the two from widening to resentment, an issue present in other popular destinations. Now, every time the visitors bureau develops a new advertisement or program, it considers how to tie in a local nonprofit or encourage visitors to be better environmental stewards, Nettles said.

Dare County has about 100 active nonprofits that do things like run attractions, work with sea turtles and organize beach cleanups — and the bureau is working to connect them with more visitors for volun-tourism opportunities, Nettles said. Many Outer Banks visitors return to their favorite island spot year after year, some for generations. Volunteering gives them a more nuanced view of what it takes to preserve the place they love and inspires them to become better stewards. And visitors who roll up their sleeves alongside residents help change the local perception of what a tourist is, making it clear they’re working on the same side.

It’s a lofty challenge to inform and motivate hundreds of thousands of new guests to be more conscious visitors every week during the summer, but Nettles said he’s optimistic about what the community can accomplish when it works together. “I would say, yeah, we're definitely having an impact, and people are feeling that,” he said.

“On the one hand, we have millions of visitors, which means you have to plan your municipal government and your systems and all that like a big city. But on the other hand, we're small towns and villages,” Nettles said. “We all know each other, and that makes us nimble. We can get together behind a shared vision and, I believe, really accomplish it. It's kind of cool. It's part of what makes this place special.”

Is destination management working?

The work seems promising so far, but it’s too early to know the true impact of destination management in the Outer Banks. Changing the way an entire industry has functioned for decades across 200 miles of different towns and counties is a slow process that takes a lot of energy on top of the day-to-day strain of the tourism sector, Knollenberg said.

“Everyone is exhausted. They've just had a hard three months getting hundreds of thousands of people through their vacations, and they don't want to think about this stuff. They wanna turn their brains off and not worry about it until it's April,” she said. “It's going to take time. It’s going to be a two steps forward, one step back kind of thing. We should have been doing this a while ago. Let's not go another 30 years …. Let's start doing this now.”

Clark Twiddy, president of Twiddy and Company — the local vacation rental business that co-launched the Lighthouse Fund — noticed the destination management idea isn’t popular with everyone. A lack of widespread support, especially while the communities were already struggling to keep up after the pandemic, kept the research from having the powerful initial impact he hoped.

“We weren’t ready to hear it,” he said. “We were so busy getting alligators out of the boat that we didn't wanna think about the alligators on the shore, which is perfectly valid.”

It can also be scary to change the way tourism is done, Twiddy said. Some might fear change will bring even more people and the local communities will become unlivable. Others might feel overwhelmed by the problems tourism brings and prefer to look away.

“How do you address fears? Not in a fear-mongering way,” Twiddy said. “That's the crossroads we are at as a community, and we're not alone. There are a lot of places in the United States from a destination tourism management side that are really struggling with that.”

Twiddy said he thinks research like this would benefit from upfront work like discussing community fears, ensuring people are ready to have a conversation about a controversial topic, and making it a collaborative effort between government agencies, nonprofits and businesses across the chain of islands.

Growing pains aside, Twiddy still believes the work is important. He used some of the Lighthouse Fund findings to inform how he helps his employees access affordable housing and schooling for their children. “I don't regret it,” he said. “It was money well spent. The findings were legit. We learned a lot.”

There are bound to be skeptics of this kind of work, Nettles said. But it’s hard to argue with results. “We have to continue to do the work, and over time, the skeptics and the cynics will become the minority.”

Though it will likely take many years to see if this work actually makes the industry more sustainable and keeps the Outer Banks livable, locals seem hopeful that this is the right way forward, celebrating the little wins along the way.

“I really do think that we can change the culture of tourism on the Outer Banks,” Nettles said. “We're doing it right now.”

Editor’s note: This story was created as a part of the Solution Journalism Network’s 2024 Climate Solutions Cohort, of which the author is a fellow.

Taylor’s work spans print, podcasts, photography and radio. She brings her passion for covering social and environmental issues through the lens of solutions journalism to her work as assistant editor.