A Corolla Light Resort sign sits on the sand dunes between the resort and the Atlantic Ocean. The dunes are some of the tallest, most intact in the Outer Banks and are covered with beneficial vegetation thanks to decades of efforts to protect them. (Image: Taylor Haelterman)

Those who call North Carolina’s Outer Banks home are used to the ever-present change that comes with life on a shifting sandbar. With a lagoon on one side, the Atlantic Ocean on the other, and no bedrock to anchor them down, the popular vacation spot and its inhabitants are at the whim of nature. They bring up beach erosion matter-of-factly, often followed by, “That’s just the way it is here.”

“We understand the fragility,” said Tameron Kugler, director of travel and tourism for Currituck County. “The Outer Banks, they call it the barrier islands, but they’re not traditional islands. They're constantly moving and have been for millennia and will continue to move. There's no way to stop it. All the beach nourishment, everything that you do will not stop the banks from moving.”

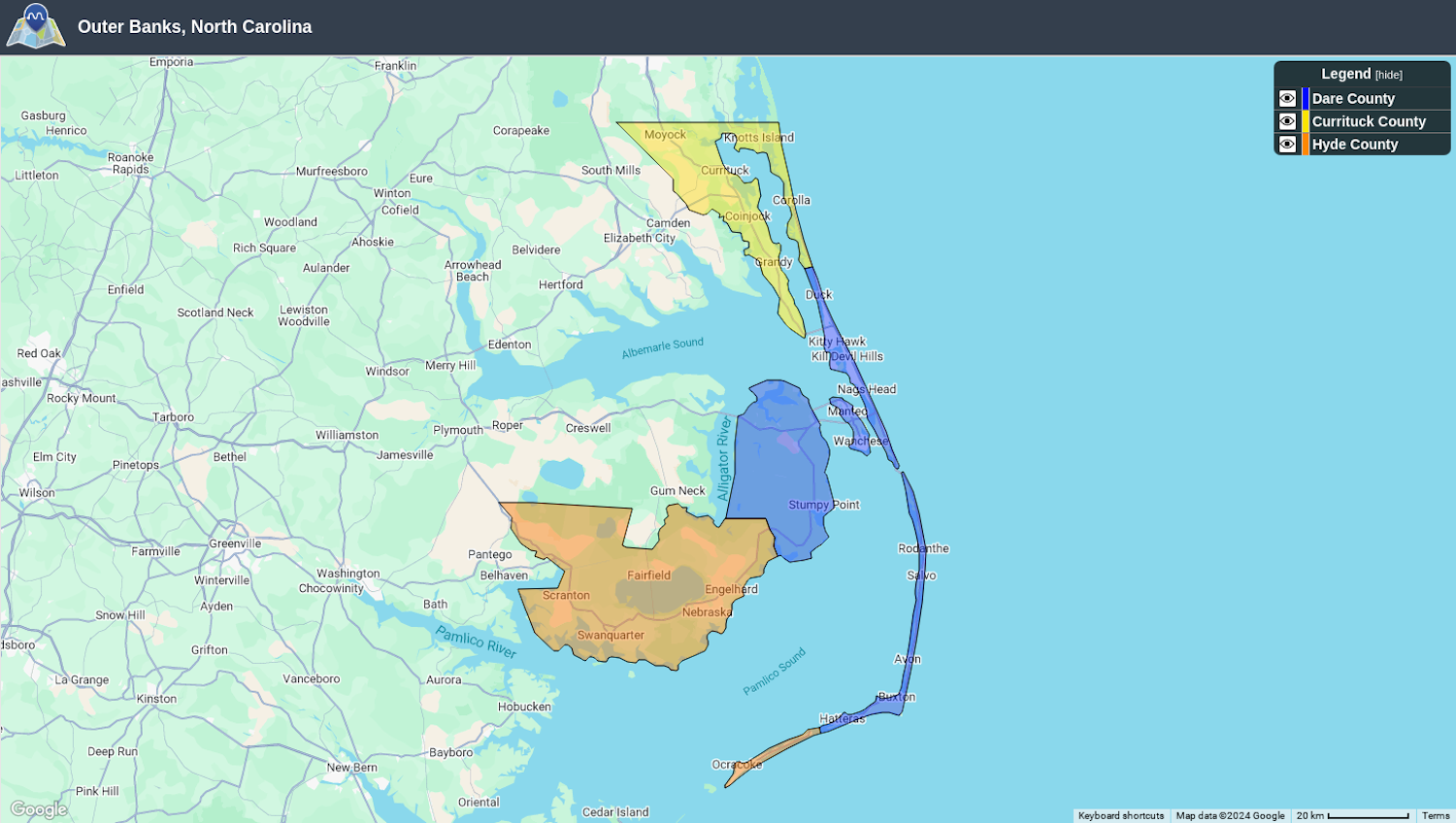

Currituck is the northernmost of the three counties spanning the 200 miles of islands off the coast of North Carolina that make up the Outer Banks. Situated on those stunning sandbars are thousands of homes and vacation rentals — the lifeblood of the tourism industry here. They dwarf the few hotels, and most people rent the same house year after year, sometimes for generations. About 20 percent of the people who visit Corolla, the northernmost town in the Outer Banks, have visited 20 times or more, and 60 percent have visited at least five times, Kugler said.

“When people come here, they really fall in love with it,” she said. ”They stay in a house, and they want that house. They don't want another house. So a lot of times, as they're checking out, they're checking in for the next season.”

The risks of vacation rentals

The precarious position of these beachfront properties has left some to be swallowed by the ocean and others to face the wrath of increasingly frequent and severe weather events. Where they are built also affects the durability of critical sand dunes that protect the shoreline and the amount of safe habitat available for wildlife — like Currituck County’s free-roam wild horse population, which has shrunk to only about 100 horses.

“Although we do the best we can to educate a tourist, they can affect the sustainability of the horse herd,” Kugler said. “You don't want to feed a horse because they are not used to what we would normally feed a domestic horse. A carrot or an apple will cause colic, which will cause intestinal twisting and bloating, which will kill them. One carrot. One apple. [If] you don't close your trash can, that horse can come up and go in your trash can.”

Still, the allure of picturesque vacation homes and beaches led to an unprecedented boom in visitation over the last few years. The small towns across the Outer Banks essentially reach maximum occupancy every summer as hundreds of thousands of people return to their favorite rentals. That influx of visitors also means more energy use, resource consumption and waste, all of which feed into larger environmental issues.

The surge in rental demand led to a proliferation of homes turned into short-term rentals for vacationers instead of long-term rentals for locals, who are left in desperate need of affordable housing as home prices reach record highs. If locals are pushed out, businesses and the tourism industry won’t survive.

“They're turning [houses] into short-term rentals, which takes that property off the market for the lower-income families who need housing,” Kugler said. “We're at the point where we don't have places for our workers. There's no place to rent for a family. We have workers coming in from two hours away.”

As the Outer Banks searches for a more sustainable way to manage tourism, vacation rentals will need to be a part of the conversation.

“How do we ensure [the owners of] these vacation homes are doing everything they can to be environmentally friendly and reduce their carbon impact?” said Whitney Knollenberg, an extension department specialist in tourism at North Carolina State University who studies sustainable tourism development in the Outer Banks. “It also comes down to the visitors themselves and awareness of what their impact is in terms of energy use, water use, things like that. If we want to really make an impact, everyone has to be a part of it.”

Building sustainability into the foundation of vacation rentals

Corolla Light Resort offers one example of a sustainability-focused vacation rental operation. The resort spans the half-mile width of the island it sits on, touching the Atlantic Ocean on one side and the Currituck Sound on the other. It hosts 450 privately owned and managed homes, over half of which are dedicated vacation rentals. When the developer, Dick Brindley, started building on the Corolla property in 1985, he was careful to preserve the unique environment that makes the place special, starting with the sand dunes along the ocean.

“The front row houses here in our community are not built right up next to the dune,” said Ben Stikeleather, the resort’s general manager. “Dune preservation and the open space that existed between the houses and the dune was a very big deal. Because of that, we have seen far less seawater intrusion or damage to property. Our dune structure stayed much healthier.”

Brindley also limited the number of stairs built over the dunes for beach access to avoid cutting through them more than necessary. Instead of building a private set of stairs for every home, residents share just five sets across the community, Stikeleather said.

“That has created a very different coastal profile than what you see, for example, in Rodanthe, where every couple of weeks now, there's a house that is washing into the ocean,” Stikeleather said, referring to a town on the southern half of the barrier islands that struggles with coastal erosion.

Though Brindley passed away in 2018 at age 90, the community carries on his desire to protect the dunes by planting sea grass and sea oats on them every year and installing sand fencing along the coastline, which stabilizes them and prevents erosion. The efforts are supported by grants from Currituck County’s cost-share program for dune plantings.

These simple development choices allowed the dunes at Corolla Light to grow to some of the tallest, most intact in the Outer Banks, benefitting the local environment and the community, Stikeleather said.

“The community immediately to our north, whenever there are strong nor'easters, has had structures like swimming pools wash into the ocean,” he said. “We've not had any of that, because of that respect for the ocean and understanding that there needs to be a setback.”

On the other side of the island, Brindley also kept housing development safely away from the lagoon. A buffer space and nature trail stretches along the entire western side of the community. Along that path, the resort installed osprey nests to support the resurging population of the once-endangered bird, and the team does its best to manage the environment with natural means. To address low-lying areas with standing water, for example, they are considering planting more native trees instead of raising the land.

The benefits these practices have on the local ecosystem are made apparent by the abundance of wildlife that can be seen in a short stroll along the property, including a bald eagle nesting site.

“Constantly trying to find ways to work with the environment that we have here, as opposed to making it do what we want it to do, is the best way I know how to say it,” Stikeleather said of the community’s philosophy.

Cementing care for the environment into the very foundation of the resort drew in homeowners who want to carry on Brindley’s vision.

“It attracted certain types of owners originally to the community, owners who really understood the uniqueness of the environment of the Outer Banks and wanted to see that preserved,” Stikeleather said. “Because of that, the new owners that come in are typically people who've been guests here, and they fell in love with that aspect of it. It takes an initial vision — without his initial vision, it wouldn't be what it is today — but then it takes people who carry that value on into the future.”

Owners and visitors actively participate in conversations about sustainability and like to know it’s staying front-of-mind, Stikeleather said. One homeowner recently turned their yard into a pollinator garden, a choice supported by the resort’s architectural review board, a far cry from how community boards often react to such changes in the United States.

Not everything comes down to the initial design, though. The management team actively makes sustainable upgrades like replacing community lights with solar-powered versions. They hope to install more renewable energy options throughout the community, adding to the geothermal system installed by Brindley in 1985 to heat and cool the on-site athletic complex.

But sustainability efforts are sometimes limited by the resort’s isolated location, Stikeleather said. Everyone shows interest in recycling, for example, but there’s no nearby market for recyclables, so it’s not a financially viable project.

An ongoing community-wide effort

As tourists’ interest in sustainability grows, and seemingly the whole of the Outer Banks joins the sustainable tourism discussion in one way or another as they cope with rising crowds and environmental hardships, more and more vacation rental businesses on the islands are working to mitigate their impact. But creating truly sustainable change across the area’s tourism industry requires the whole community. Local vacation rental businesses are an important voice but should not be overly represented in the conversation — like they often were thanks to a tourism model that relies on funding from lodging taxes, North Carolina State University’s Knollenberg said.

“They need to be a part of that conversation, but they're not the only stakeholders in this industry,” she said. “There's a lot of others that have to be a part of that. It's a lot of structural change. It's a lot of change in what we prioritize. And that just takes a lot of energy and time.”

Even with sustainable change, there’s no way to stop the shifting of the sand below their feet.

Though decades of forward-thinking left Corolla Light in better shape than some properties on the islands, the management team must keep nursing the health of its shorelines every year and constantly thinks about improving extreme weather resilience, Stikeleather said. Recognizing that storms and erosion are a part of life, the best they can do is mitigate the negative impacts they’ll face while maintaining a positive environmental impact.

“Dick Brindley developed a plan here that will last for a very long time,” Stikeleather said. “But it is difficult for anything to last forever on the Outer Banks.”

Editor’s note: This story was created as a part of the Solution Journalism Network’s 2024 Climate Solutions Cohort, of which the author is a fellow.

Taylor’s work spans print, podcasts, photography and radio. She brings her passion for covering social and environmental issues through the lens of solutions journalism to her work as assistant editor.