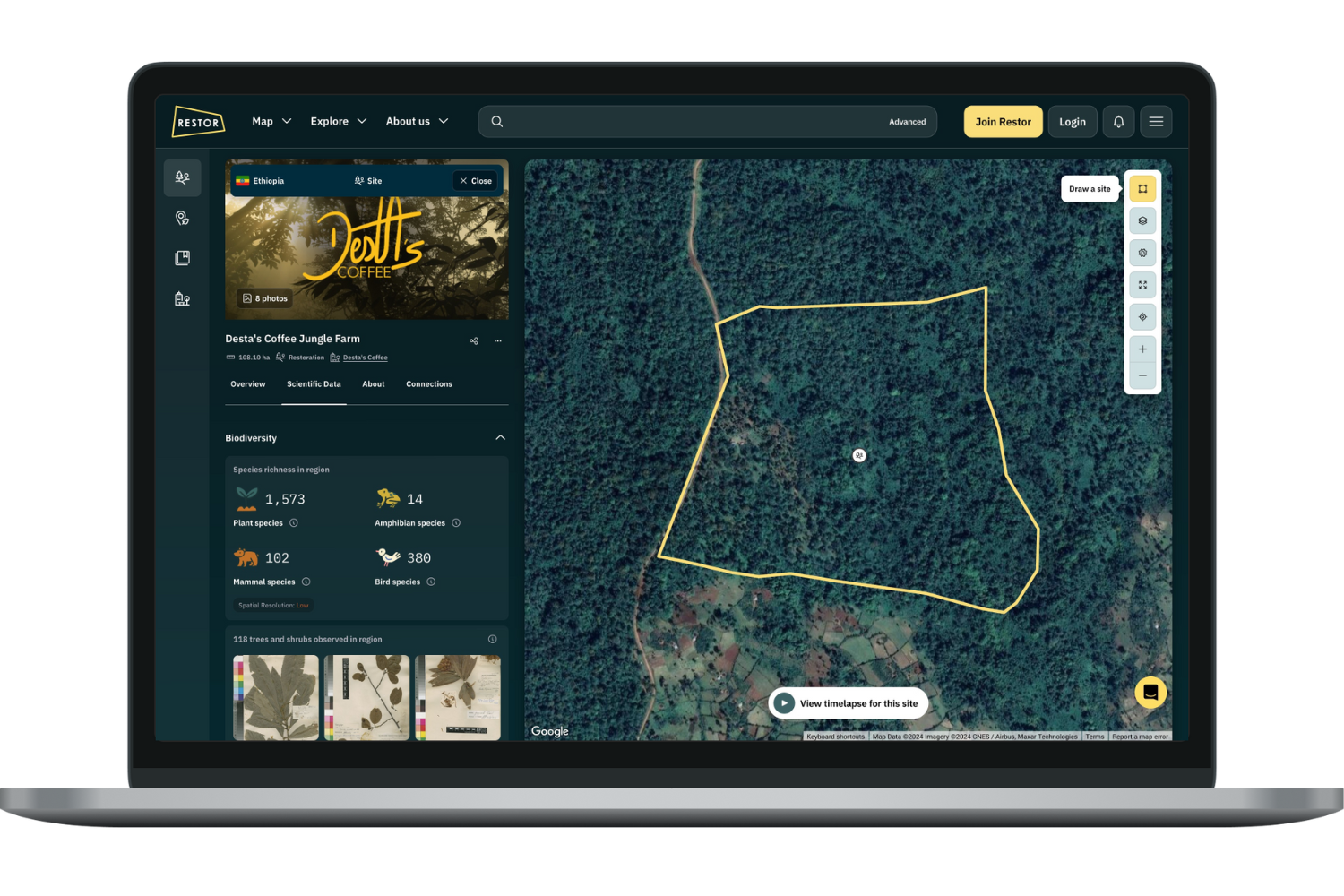

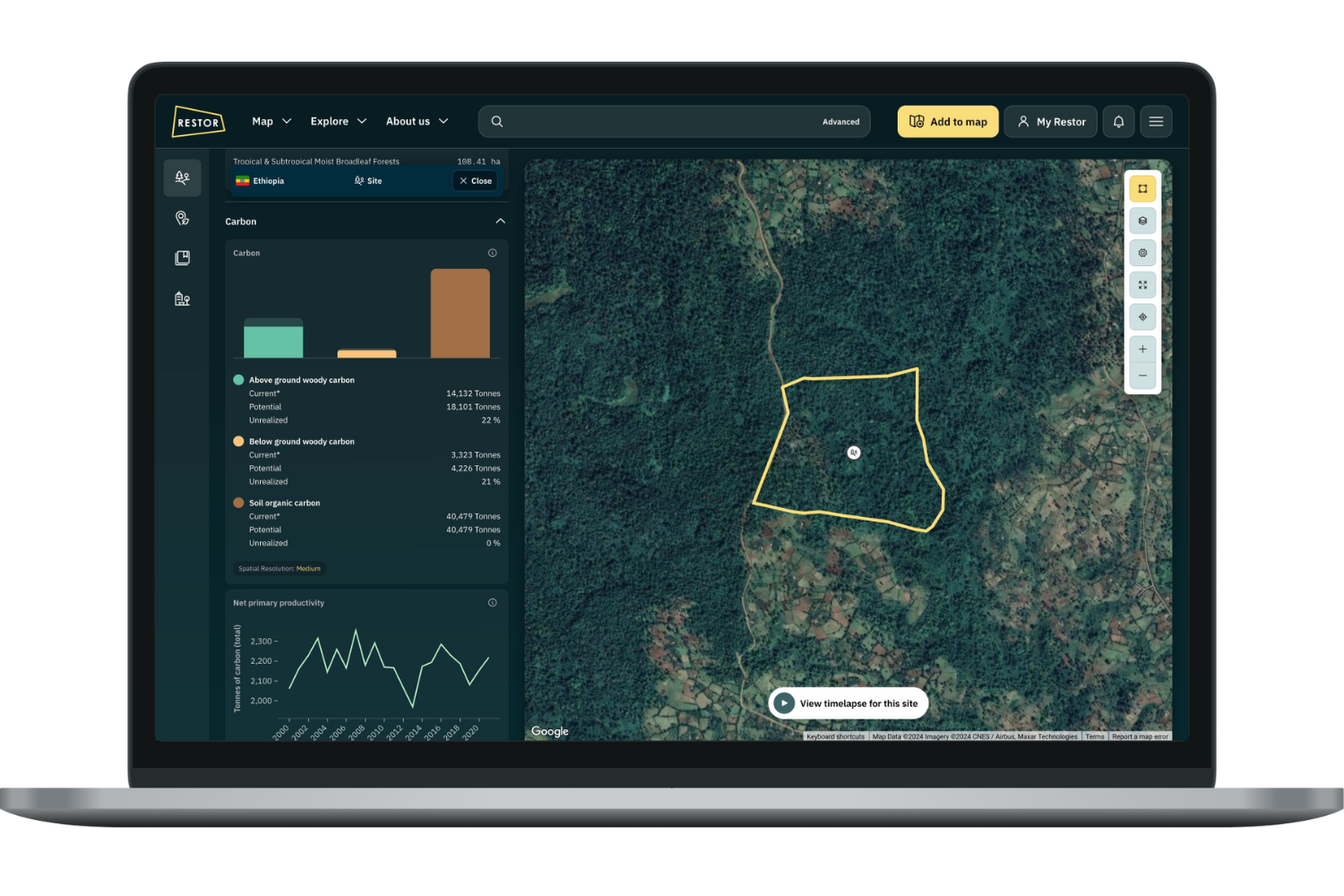

The Restor platform hosts a variety of information on locally-run restoration sites and includes a marketplace for land stewards to advertise the products and services that fund their work. (Image courtesy of Restor.)

With our burgeoning population and sprawling cities, it’s no surprise that humans use the majority of terrestrial land globally. And we haven’t exactly been good occupants. We’re degrading ecosystems from farmlands to forests. Land degradation impacts 3.2 billion people, nearly 40 percent of the world’s population. This fuels the loss of ecosystem services worth over 10 percent of our annual global economic output.

To combat this downward spiral, the United Nations Environment Program wants one billion hectares of land to be restored by 2030. But rehabilitating an area approximately the size of China isn’t easy.

However, there’s a ray of light in the degradation darkness: Restor. Part social network, part marketplace, Restor is a global, open-access restoration platform. Started in 2020, it already boasts over 21,000 users and organizations on its roster. While designed to help the environment, this platform firmly places people first.

The social side of restoration

Land degradation isn’t a level playing field. Much like leafy trees blanket wealthy neighborhoods more than lower-income ones, degradation disproportionately affects Indigenous groups, women, children and people with incomes below the poverty line.

“The underlying driver of degradation, we believe from recent research, is actually inequality,” said Thomas Crowther, a professor of ecology at ETH Zurich, a public research university in Switzerland, and founder of Restor. “We have very rich people with huge footprints. And we have billions of people who are living most closely in association with nature, living below the poverty line, living without the resources that they need to live sustainably. They are forced to live day-to-day, and they have no non-extractive options.”

Degraded areas cause numerous problems. For instance, they threaten agriculture and food security, and air pollution contributes to over eight million deaths per year. And that’s not all.

“There are already millions of people experiencing the devastation of climate change and biodiversity loss,” Crowther said. “Heat-related morbidity and mortality are the highest climate-related drivers of death, and that is being faced by billions of people in the global south who are vulnerable to these growing threats.”

Restoration can turn this ship around by fighting global warming while aiding in climate adaptation. For instance, restoring ecosystems can reduce erosion, flooding, and storm surges while cooling temperatures, especially in urban areas. Restoring natural environments also reduces air pollution, provides clean water, improves food security and prevents biodiversity loss.

What Restor offers

With an array of online tools, Restor is tackling the mismatch between healthy ecosystems and degraded ones.

“Our hypothesis was that, actually if we can find and distribute wealth to those local stewards of the people living with nature, that is our best opportunity for ecological recovery,” Crowther said. “That was the mission for Restor — to build a single platform that finds and empowers millions of local stewards of nature.”

Started by Crowther’s lab at ETH Zurich, Restor is now an independent nonprofit organization. The platform covers 209,000 sites worldwide, ranging from grazing land restoration in the United Kingdom to lake rehabilitation in Nepal. And it’s easy to use.

“As a farmer, I can draw out my farm, and I immediately get information about the ecology of the farm,” Crowther said. “I learn about the species that naturally live there. I learn about the carbon that's stored there and the water and how these things are changing.”

In addition to these factors, users get information about land and tree cover, tree loss over time, biomass, human populations, and other climatic and site measurements. Much like Google Earth, you can zoom into sites for a detailed view and watch time-lapse videos.

All this data can help users manage their land by showing regions with the potential for carbon storage or conversely erosion, for example. But Crowther emphasizes the platform’s goal is to share information and not prescribe what landowners should do.

Restor’s marketplace

Besides learning about their land, Restor users can connect with funders, some of whom already advertise on the platform, Crowther said. And they can reach customers for their products or services.

“In the same way you would use Google Maps, you can find coffee to buy, or you can find holidays to go on or whatever else,” Crowther said. “It's just that you can actually see where those products come from [on Restor].”

One coffee grower’s profits increased by 600 percent after joining Restor and creating a QR code. The code, which let customers see exactly where their coffee is coming from, promoted sales.

“My dream is that you've walked down a supermarket aisle, and you can scan your cereal, and you see where it came from,” Crowther said. “It doesn't need to come from a good project or a bad project, but at least you see it. And that gives you agency to then choose what kind of cereal you want based on its flavor, but also based on its environmental footprint.”

Besides products and services, Restor could help with another tricky market — the one for carbon. While cabon credits have been problematic at times, Restor would boost transparency by allowing potential buyers to see the sites they stem from. It could also used for biodiversity credits, where a buyer pays to conserve or restore a certain amount of land.

While the platform has a lot of potential, not all of its sites are very healthy or diverse ecosystems. The organization wants both good and bad projects on Restor. It hopes that by doing so landowners can learn from their successes and failures.

The future of Restor

Despite Restor’s impressive record so far, there’s even more coming down the platform’s pipeline. It plans to add bioacoustics data, so when users click on a site, they can actually hear the area’s sounds, Crowther said. This information is useful since the soundscape of an ecosystem can accurately predict habitat quality and biodiversity.

Further, its launching a new way to display portfolios and projects later this year.

“A government could display all 100,000 sites in their country and show the footprint of that nation and how it's progressing,” Crowther said. “The same way a company can display 100,000 sites that they source from, and that would show their aggregated footprint.”

The organization is also working on a verification process for land ownership. While not currently a problem, Crowther is concerned about misuse of the platform as it scales up.

The power of restoration

Restoration is one of the smartest things we can do. Every $1 invested in restoration can generate up to $30 in economic benefits. Plus, it’s one of the rare actions that simultaneously benefits the economy, the environment, human health and food security.

Restor already covers 167 million hectares of restoration projects — an area nearly the size of Alaska — and it’s growing. By giving users the tools and funding they need to restore their land, Restor recognizes the essential link between the environment and people.

“If our society plans to continue in the long term, we just fundamentally have to limit climate change and biodiversity loss,” Crowther said. “It's a global thing, but more urgently, I actually think it's essential for the people who are facing those threats right now.”

Ruscena Wiederholt is a science writer based in South Florida with a background in biology and ecology. She regularly writes pieces on climate change, sustainability and the environment. When not glued to her laptop, she likes traveling, dancing and doing anything outdoors.