Colombia’s high-altitude wetland region known as the páramo. (Image: Quimbaya/Flickr)

As the world transitions toward renewable energy sources, the demand for minerals important in developing those technologies is surging. Minimizing the negative social and environmental impacts of mining, while maximizing the positive benefits of renewable technologies, is a difficult yet critical balancing act. Finding harmonious solutions to this dilemma is the focus of TriplePundit's series on responsible mining in the energy transition.

The World Bank’s private lending institution, the International Finance Corporation, invested $14.4 million in the Canadian mining company Eco Oro Minerals Corp. from 2009 to 2010. The company was poised to develop a gold mine in Colombia’s Santander region in the high-altitude wetlands known as the páramo.

The páramo regions in Colombia provide the country with 70 percent of its drinking water. Locals had major concerns about the protection of those water sources, particularly from cyanide pollution, as gold mining operations and large cyanide spills have led to environmental disasters in Romania, Mexico, Argentina and Turkey. Nonetheless, the mine was set for development, and it was only when a process unique to development finance institutions was invoked that the local communities, led by the organization Comité para la Defensa del Agua y del Páramo de Santurbán, were able to have their concerns addressed.

Using the International Finance Corporation’s independent accountability mechanism, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman, the Colombian communities were able to open an investigation into the proposed mine. The process eventually resulted in the International Finance Corporation’s divestment from the project.

While gold is not critical to renewable energy technologies, the process of raising concerns with development finance institutions to trigger an investigation will be important for communities facing adverse impacts from mining projects to meet the needs of the low-carbon energy transition.

What are development finance institutions?

“Development finance institutions, or development banks, were created after the Second World War to assist European countries in recovery and development,” explains Carla Garcia Zendejas, director for people, land and resources at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL). The nonprofit law organization worked with Colombian communities to file grievances against the International Finance Corporation and Eco Oro.

What makes development banks different from regular commercial banks is that they are owned by national governments and have rigid environmental and social policies. In countries where political situations or the economy are unstable, investments may be too risky for private interests, so development finance institutions step in to provide funding. There is no mandate that says funds must go to local businesses, making international companies the common recipients of development bank funding, much like the Canadian company Eco Oro in Colombia.

Development banks can be owned by a single country or a group of countries. Some of the world’s largest development banks include the World Bank, the European Investment Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the InterAmerican Development Bank, and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation.

What role do development banks play in mining projects?

Along with financing, development banks conduct environmental and social assessment processes for all projects they engage in, bringing added transparency and accountability to these projects.

As many transition mineral deposits are located in countries where private investment carries additional risk, development banks will play an important role in bringing these critical minerals to market.

Unfortunately, the environmental and social assessments are not always thorough, and project funding can be approved with meager consultation and review.

“Something we’ve seen as a consequence of the pandemic, unfortunately, is that a lot of the progress we had been making for proper human rights due diligence and environmental assessments went out the window when financing began getting fast-tracked,” says Garcia Zendejas. While those measures were meant to be temporary, many recent assessments were still just going through desk reviews, receiving approval without proper environmental and social due diligence, she says.

Although there are problems with mining projects and the assessment process of development banks, communities have more options when a development finance institution is involved, because it provides more avenues for seeking justice and more transparency into which actors are funding a project, Garcia Zendejas explains.

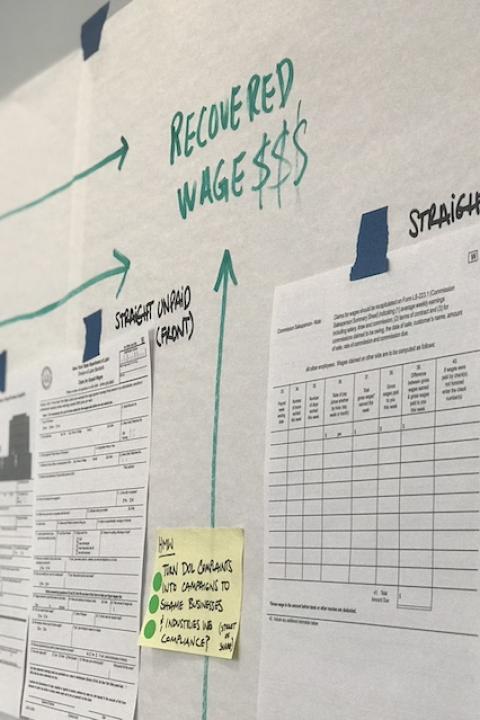

Assessment procedures vary between development banks, but because of human rights violations associated with development bank projects, all of them now have an independent accountability mechanism that allows for complaints to be raised and investigated.

Independent accountability mechanisms offer an avenue for justice

Independent accountability mechanisms are a separate arm of development banks that investigate complaints they receive from communities or organizations impacted by development projects.

For example, the accountability mechanism of the European Investment Bank is called the Complaints Mechanism.

“Our work focuses on maladministration of the [European Investment Bank]," says Omar El Sabee, acting head of the bank’s Complaints Mechanism Division. “Maladministration happens when the [bank] does not comply with its own standards and policies. Any person who feels impacted by any action of the bank can complain.”

Most development banks have strong environmental and social policies, but the question is how well those policies are implemented. The Complaints Mechanism at the European Investment Bank handles about 90 to 100 complaints per year, ranging from governance or access to information cases to complaints about the environmental and social impacts of projects. However, only a fraction of those complaints are found to be grounded.

During a compliance review, the Complaints Mechanism investigates whether the bank has correctly followed its own policies. Where appropriate, complainants may be offered the opportunity to resolve their issues through a dispute resolution process with the company running the development project.

In some cases, projects are halted or remediation is issued to impacted persons and communities as a result of an accountability mechanism process. It can be difficult to reach that stage, but when banks or companies are found to have operated with negligence, they do have to face consequences.

How accessible are independent accountability mechanisms?

Each development bank has different accountability procedures. One of the reasons why the European Investment Bank says it receives a higher number of complaints than other development banks is that its Complaint Mechanism is built to be accessible. However, there is always room for improvement.

“When complainants come to us, they think that we can immediately help them or that we can stop the project. We don’t have that power,” says Laurence Levaque, who shares the role as acting head of the bank’s Complaints Mechanism Division with El Sabee. “If we find project non-compliance, eventually our recommendations will trickle down and there will be changes on the ground, but it’s a long process.”

The recommendations that the Complaints Mechanism deliver are not legally binding, however their implementation is monitored, made public, and both the bank and the company take the recommendations very seriously.

While some independent accountability mechanisms will only accept complaints by directly impacted persons and require that multiple persons corroborate each complaint, the European Investment Bank’s process allows for anyone to raise concerns, and only one person needs to file a complaint to trigger the assessment process.

“Some accountability mechanisms also require the complainant to indicate which law or standard was breached,” El Sabee says. “For us, we don’t require complainants to be knowledgeable about our policies or standards. It’s enough that the person feels impacted, and it’s on us to analyze which policy or standard was not respected.”

As well, some mechanisms require that the complainant first raise the issue to the company leading the development project before proceeding to the development bank’s accountability mechanism. At the European Investment Bank, complainants can go straight to the Complaints Mechanism without consulting the company in charge of the project.

'Just do the right thing’ from the start

Development banks generally have strong policies to protect people and the environment from harm, but those policies need to be followed for them to be effective.

“You have the standards, just do the right thing,” says Garcia Zendejas, directing her words toward development banks. “You want to go in there and start a project? Fine, but follow all the policies that you have in place. Don’t wait for the company to say, ‘Oh no, I couldn’t do the consultation,’ or, ‘I couldn’t find the Indigenous peoples.’ Most of the banks have pretty good environmental and social governance systems. The problem is just a lack of implementation. When you fail, resulting in harm to communities, you must take responsibility and remedy the harm.”

In the case of the Eco Oro gold mine in the Colombian páramo, with the help of the Center for International Environmental Law, the community succeeded in having the International Finance Corporation divest from the project. The divestment, along with a series of events in Colombia — including a denied environmental license and court decisions confirming laws that banned mining in the páramo — halted the mine indefinitely.

Eco Oro, unhappy with that decision, then sued the Colombian government for about $700 million, citing lost profits from the blocked mine. The international arbitration tribunal eventually found Eco Oro entitled to damages in 2021, but a final decision on the amount is still being determined.

The community, however, considers it a victory. In the case of Eco Oro, they blocked the mine and forced the International Finance Corporation to divest from the project. Despite this success, they continue to face threats from new companies looking to develop mines in the same region.

While imperfect, independent accountability mechanisms serve a valuable purpose. Ideally, development banks would follow their own policies and conduct thorough assessments and consultations for every project, but at the very least, there is a process that impacted persons and communities can use to contest the validity of those assessments.

This process is only available to projects that receive funding or investment from a development finance institution, but it is a viable way to reduce the social and environmental harms of mining as the world ramps up the low-carbon energy transition.

Andrew Kaminsky is a freelance writer with no fixed location. He travels all corners of the globe learning about the different groups that call this planet home, seeing natural wonders, and sharing laughs with the people he finds along the way. An alum of the University of Winnipeg's International Development program, Andrew is particularly interested in international relations and sustainable development. In his spare time you are likely to find Andrew engaging in anything sport-related, or finding common ground with new friends over a craft beer.