The death of a Nevada woman has focused renewed attention on the problem of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The woman, who died in September after returning from a trip to India, contracted a bacterial infection that successfully resisted every FDA-approved treatment.

The incident was reported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last week, only a few days after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced a set of new rules aimed at fighting these so-called "superbugs" on their home-turf: the farm.

Under those regulations, which went into effect Jan. 1, meat producers will no longer be allowed to use antibiotics to help livestock gain weight. And they will be required to obtain veterinary approval before using the drugs for other purposes.

The change — decades in the making — was lauded by many as an important step forward, while others decried it as too little, too late.

The Natural Resources Defense Council, which previously sued the FDA over the issue, equated the agency's actions with "putting lipstick on a pig."

"For decades, FDA has been allowing antibiotics to be used en masse at low doses for both growth promotion and so-called 'disease prevention' in the unsanitary living conditions on many industrial farms," NRDC Senior Attorney Avinash Kar said in a prepared statement.

"Today’s announcement eliminates language on antibiotics labels that says they can be used for one of those purposes — growth promotion. But, and this is a huge BUT, it leaves behind a massive loophole in not addressing the other misuse — 'disease prevention.'”

The end result, Kar said, would be the same: the continued proliferation of drug-resistant bacteria.

Antibiotic resistance is a threat to public health

The use of antibiotics in the meat industry has been widely blamed for the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in recent decades.

Sustained contact with low doses of the drugs accelerates the microbes' evolution — killing off those strains that are vulnerable to the drugs while allowing drug-resistant genes to survive and multiply. The resulting superbugs can then be transmitted to humans through contact with infected meat or feces.

The problem is an urgent one. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have classified antibiotic-resistant bacteria as one of the top seven threats to public health for 2017. Such bacteria already claim an estimated 700,000 lives worldwide each year. The U.K. government has warned this number could increase to 10 million by 2050 if current trends continue.

But the problem is not new. In fact, scientists have known about it for decades. All the way back in 1977, the FDA attempted to curtail the use of antibiotics on the farm — an effort that was derailed by Congress.

While lawmakers ignored the problem, the threat only grew more urgent. Last year, scientists were alarmed to find a person infected with a strain of bacteria resistant to colistin, the so-called "drug of last resort." It was the first such case to be documented in the United States and led researchers to predict the emergence of a "pan-drug resistant bacteria." Now, it would seem, those doomsday predictions could be coming true.

The private sector can lead the way

In the absence of government action, some private businesses have stepped in to fill the gap — refusing to purchase meat from suppliers that use antibiotics in their operations.

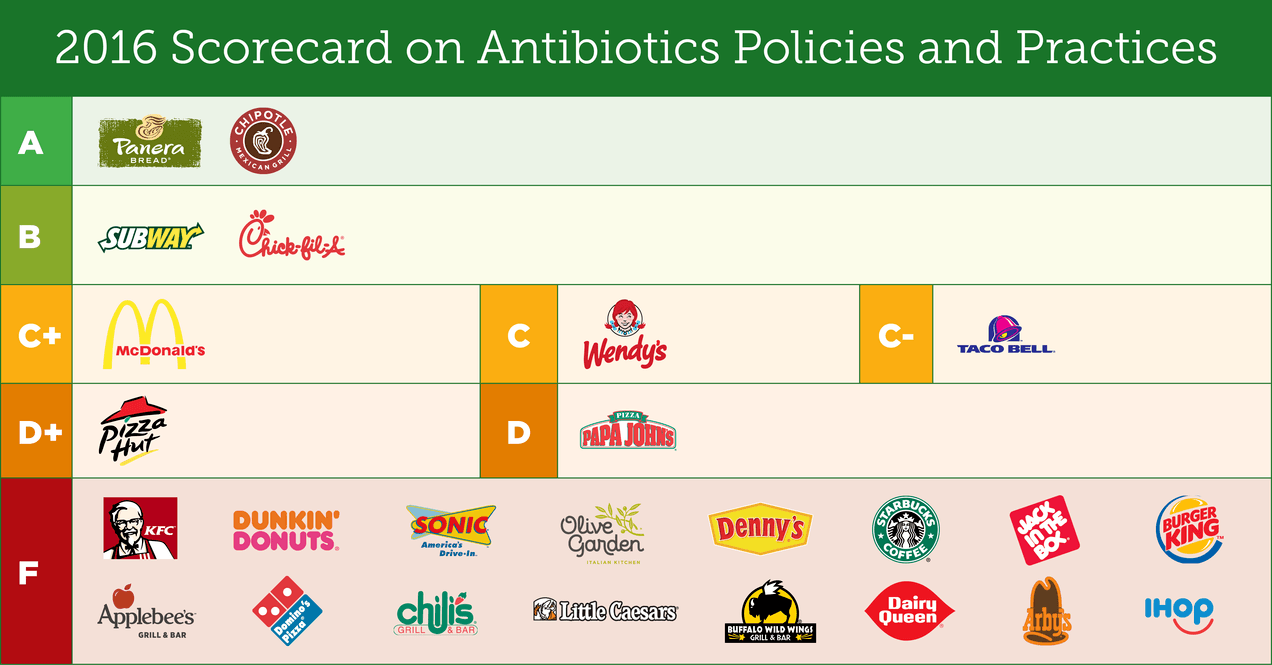

Last year, a consortium of environmental and consumer-advocacy groups released a report rating the top 25 restaurant chains on their commitment to limiting antibiotic use.

Of those surveyed, nine received a passing grade. That number might seem small, but it is twice as many as the prior year. Among these, Panera Bread and Chipotle were the only chains to receive solid “A” grades — meaning they had implemented comprehensive policies that restricted antibiotics use across their supply chains. Burger King and Kentucky Fried Chicken were among those that received a failing grade.

“This year’s progress is encouraging," Cameron Harsh of the Center for Food Safety said in a press release announcing the report. "But companies and consumers can only move the dial so far — it is time for the U.S. government to step up and mandate reductions in antibiotic use for the industry writ large.

"Without strong, enforceable regulations for antibiotic use in place, there is undue burden on the public to hold companies to their commitments and to pressure the laggards in the industry to stop dragging their feet."

Image credits: 1) and 2) U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 3) Natural Resources Defense Council

T.S. Strickland is the founder of Neon Tangerine — a branding, strategy and experience shop focused on food, tech and social good. His writing has appeared in Impact Alpha, Entrepreneur, the Food Rush and elsewhere.